Lecture 04-2: Data Science at the Command Line

DATA 503: Fundamentals of Data Engineering

February 2, 2026

Introduction to Data Science at the Command Line

The command line has been around for over 50 years, yet it remains one of the most powerful tools for CS, DS, and beyond! Today we explore why.

Why the Command Line?

Data Science Meets Ancient Technology

How can a technology that is more than 50 years old be useful for a field that is only a few years young?

Today, data scientists can choose from an overwhelming collection of exciting technologies:

- Python, R, Julia

- Apache Spark

- Jupyter Notebooks

- GUI-based tools

And yet, the command line remains essential. Let us understand why.

Five Advantages of the Command Line

The command line offers five key advantages for data science:

| Advantage | Description |

|---|---|

| Agile | REPL environment allows rapid iteration and exploration |

| Augmenting | Integrates with and amplifies other technologies |

| Scalable | Automate, parallelize, and run on remote servers |

| Extensible | Create your own tools in any language |

| Ubiquitous | Available on virtually every system |

The Command Line Is Agile

Data science is interactive and exploratory. The command line supports this through:

Read-Eval-Print Loop (REPL)

- Type a command, press Enter, see results immediately

- Stop execution at will

- Modify and re-run quickly

- Short iteration cycles let you play with your data

Close to the Filesystem

- Data lives in files

- Command line offers convenient tools for file manipulation

- Navigate, search, and transform data files easily

The Command Line Is Augmenting

The command line does not replace your current workflow. It amplifies it.

Three ways it augments your tools:

- Glue between tools: Connect output of one tool to input of another using pipes

- Delegation: Python, R, and Spark can call command-line tools and capture output

- Tool creation: Convert your scripts into reusable command-line tools

Every technology has strengths and weaknesses. Knowing multiple technologies lets you use the right one for each task.

The Command Line Is Scalable

On the command line, you do things by typing. In a GUI, you point and click.

Everything you type can be:

- Saved to scripts

- Rerun when data changes

- Scheduled to run at intervals

- Executed on remote servers

- Parallelized across multiple cores

Pointing and clicking is hard to automate. Typing is not.

The Command Line Is Extensible

The command line itself is over 50 years old, but its tools are being developed daily.

- Language agnostic: tools can be written in any programming language

- Open source community produces high-quality tools

- Tools can work together

- You can create your own tools

The Command Line Is Ubiquitous

The command line comes with any Unix-like operating system:

- macOS

- Linux (100% of top 500 supercomputers)

- Windows Subsystem for Linux

- Cloud servers

- Embedded systems

This technology has been around for more than five decades. It will be here for five more.

The OSEMN Model

Data Science Is OSEMN

The field of data science employs a practical definition devised by Hilary Mason and Chris H. Wiggins [1].

OSEMN (pronounced “awesome”) defines data science in five steps:

- Obtaining data

- Scrubbing data

- Exploring data

- Modeling data

- iNterpreting data

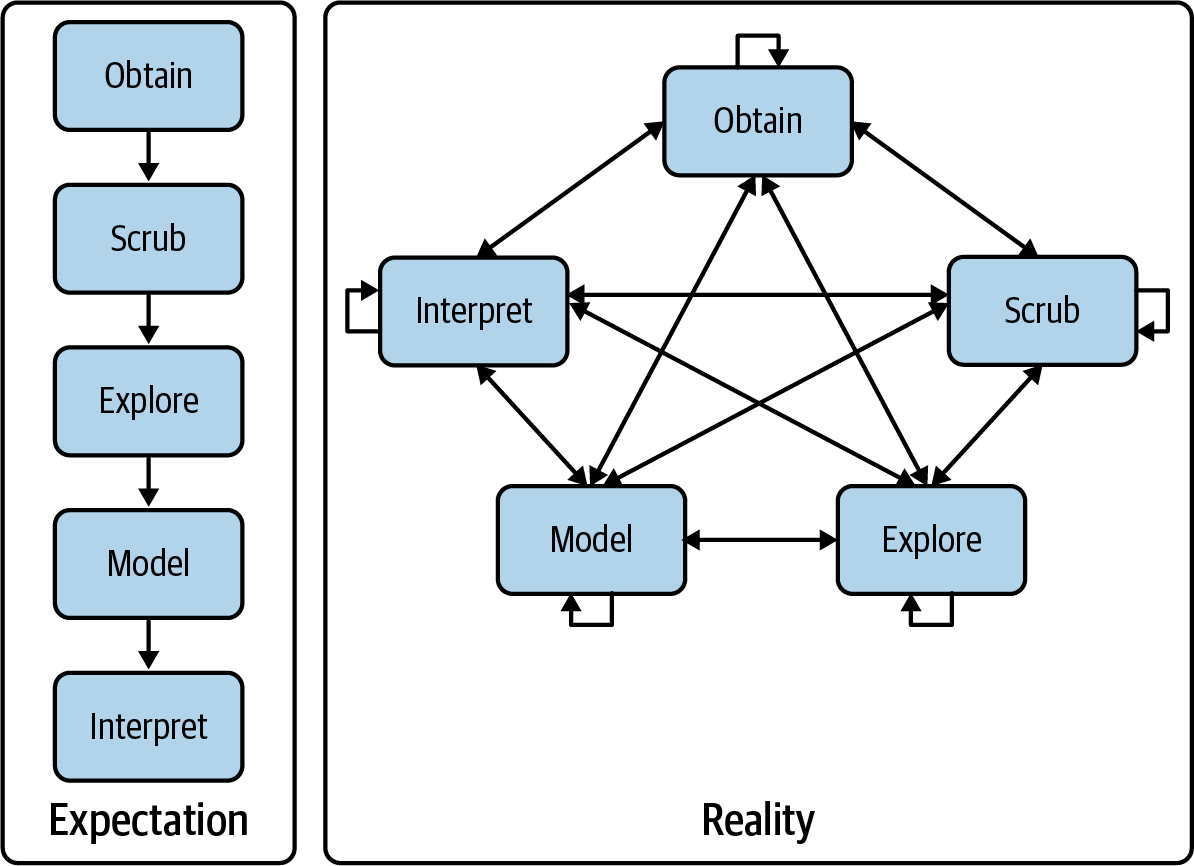

OSEMN: Expectation vs Reality

The OSEMN model shows data science as an iterative, nonlinear process

In practice, you move back and forth between steps. After modeling, you may return to scrubbing to adjust features.

The OSEMN Steps

Download, query APIs, extract from files, or generate data yourself.

Common formats: plain text, CSV, JSON, HTML, XML

Clean the data before analysis:

- Filter lines

- Extract columns

- Replace values

- Handle missing data

- Convert formats

80% of data project work is in cleaning the data.

Get to know your data:

- Look at the data

- Derive statistics

- Create visualizations

Create statistical models:

- Clustering

- Classification

- Regression

- Dimensionality reduction

Draw conclusions, evaluate results, and communicate findings.

This is where human judgment matters most.

Getting Started

Setting Up Your Environment

Docker: Your Portable Environment

We use Docker to ensure everyone has the same environment with all necessary tools.

What is Docker?

- A Docker image bundles applications with their dependencies

- A Docker container is an isolated environment running an image

- Like a lightweight virtual machine, but uses fewer resources

Why Docker for this course?

- Consistent environment across Windows, macOS, and Linux

- All tools pre-installed and configured

- No dependency conflicts

- Easy to reset if something goes wrong

Installing Docker

Download Docker Desktop from docker.com

Install and launch Docker Desktop

Open your terminal (or Command Prompt on Windows)

Pull the course Docker image:

Running the Docker Container

Run the Docker image:

You are now inside an isolated environment with all the necessary command-line tools installed.

Test that it works:

Mounting a Local Directory

To get data in and out of the container, mount a local directory:

The -v option maps your current directory to /data inside the container.

Exiting the Container

When you are done, exit the container by typing:

The container is removed (due to --rm flag), but any files you saved to the mounted directory persist on your computer.

What Is the Command Line?

The Terminal

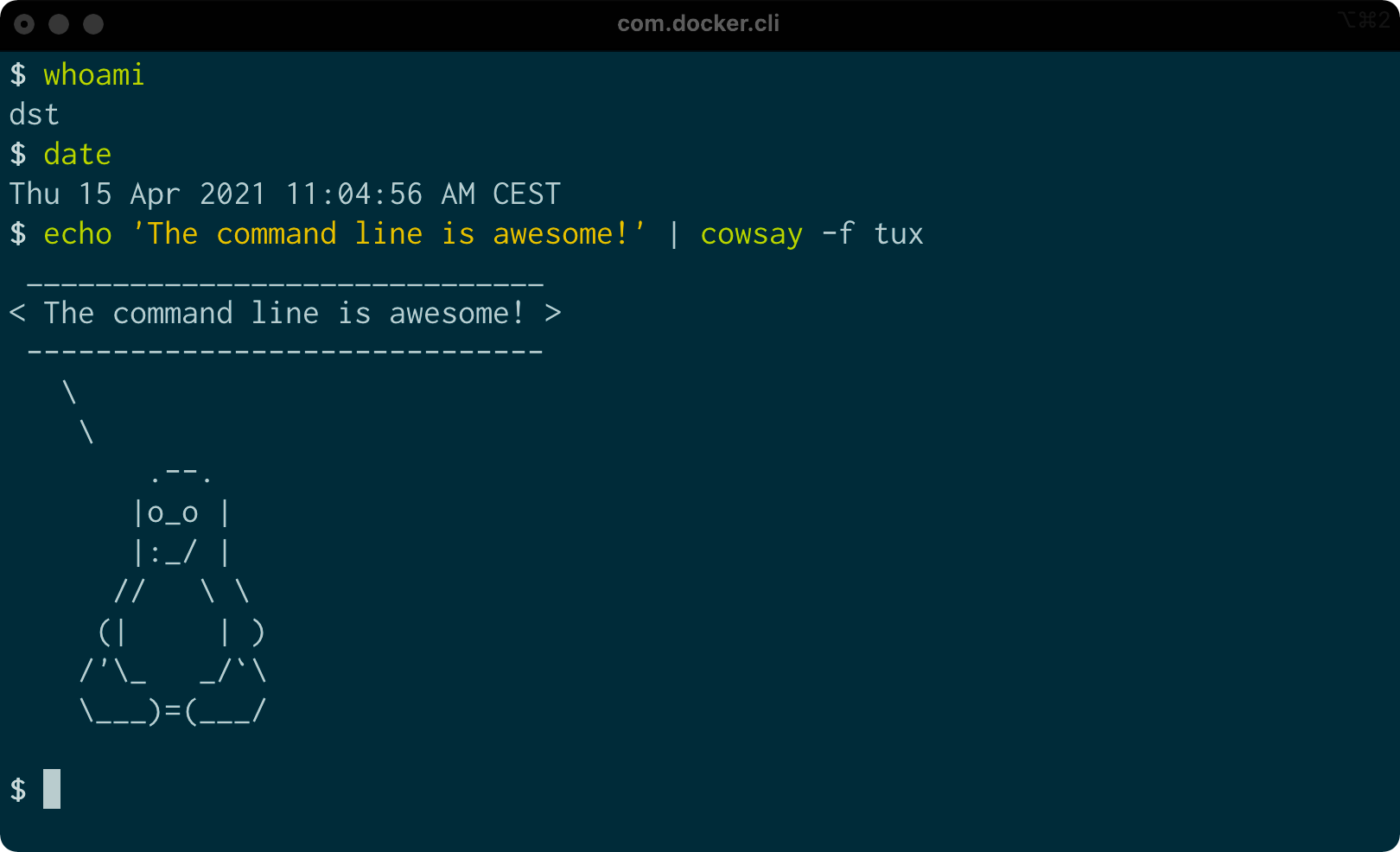

Command line on macOS

The terminal is the application where you type commands. It enables you to interact with the shell.

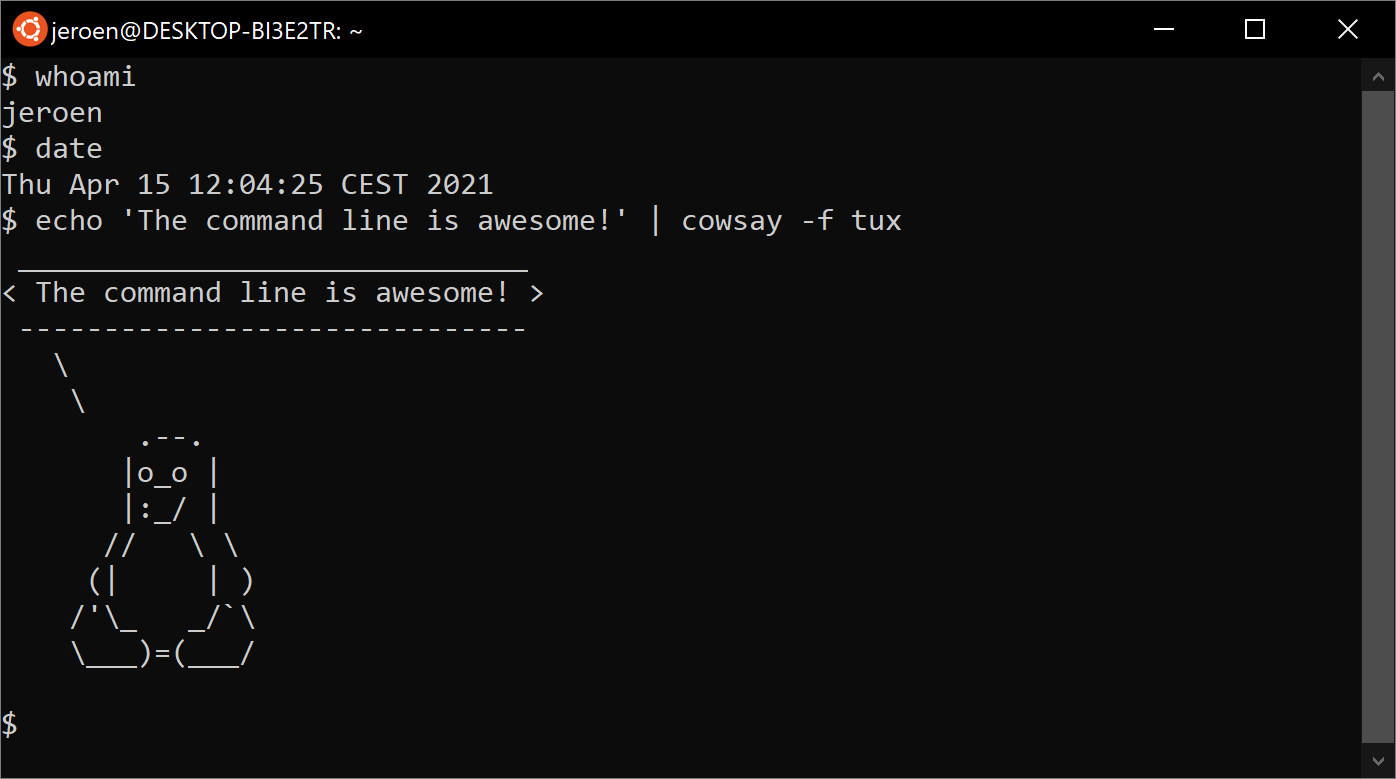

The Terminal on Linux

Command line on Ubuntu

Ubuntu is a distribution of GNU/Linux. The same commands work across different Unix-like systems.

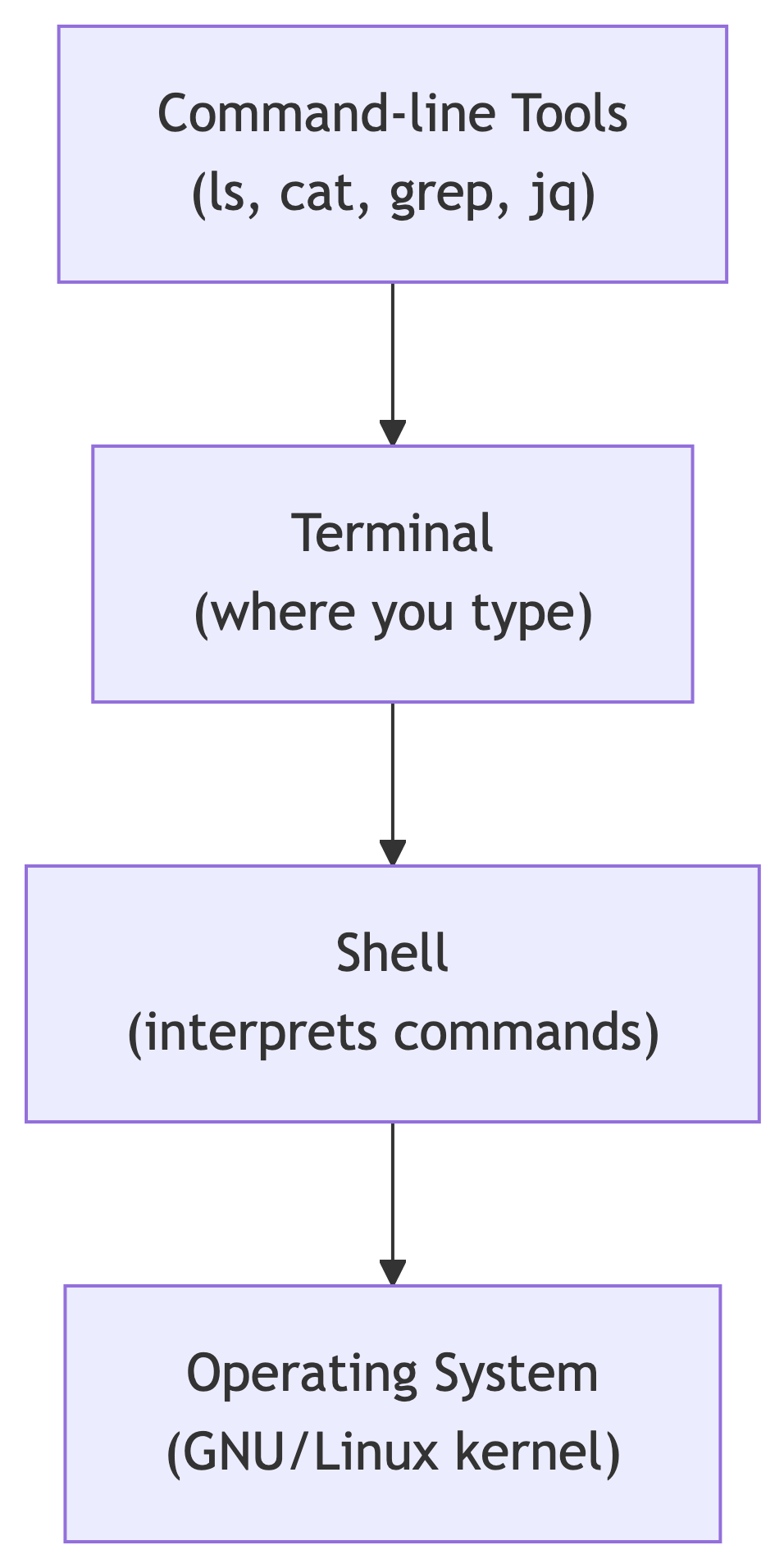

The Four Layers

The environment consists of four layers:

| Layer | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Command-line tools | Programs you execute |

| Terminal | Application for typing commands |

| Shell | Program that interprets commands (bash, zsh) |

| Operating system | Executes tools, manages hardware |

Understanding the Prompt

When you see text like this in the book or slides:

- The

$is the prompt (do not type it) seq 3is the command you type1,2,3is the output

The prompt may show additional information (username, directory, time), but we show only $ for simplicity.

Essential Unix Concepts

Executing Commands

Your First Commands

Try these commands in your terminal:

The tool pwd outputs the name of your current directory.

The tool cd changes directories. Values after the command are called arguments or options.

Command Arguments and Options

Commands often take arguments and options:

This command has three arguments:

| Argument | Type | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

-n |

Option (short form) | Specifies number of lines |

3 |

Value | The number of lines to show |

movies.txt |

Filename | The file to read |

The long form of -n is --lines.

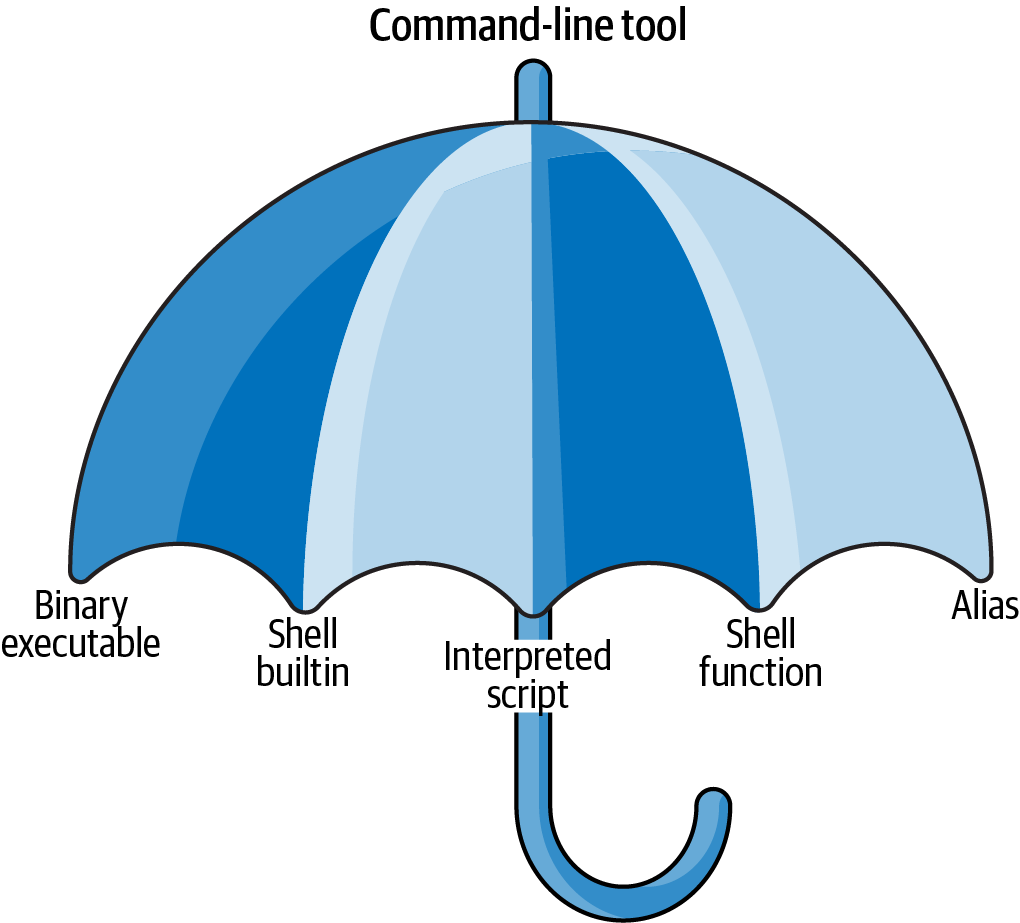

Five Types of Command-Line Tools

The Tool Umbrella

Each command-line tool is one of five types:

- Binary executable

- Shell builtin

- Interpreted script

- Shell function

- Alias

Binary Executables

Programs compiled from source code to machine code.

- Created by compiling C, C++, Rust, Go, etc.

- Cannot read the file in a text editor

- Fast execution

- Examples:

ls,grep,cat

Shell Builtins

Command-line tools provided by the shell itself.

- Part of the shell (bash, zsh)

- May differ between shells

- Cannot be easily inspected

- Examples:

cd,pwd,echo

Interpreted Scripts

Text files executed by an interpreter (Python, R, Bash).

Advantages: Readable, editable, portable

Shell Functions

Functions executed by the shell itself:

- Similar to scripts but typically smaller

- Defined in shell configuration (

.bashrc,.zshrc) - Good for personal productivity shortcuts

Aliases

Macros that expand to longer commands:

Now typing l expands to the full ls command with options.

- Save keystrokes for common commands

- Fix common typos

- Cannot take parameters (use functions for that)

Identifying Tool Types

Use the type command to identify what kind of tool you have:

Combining Tools

The Unix Philosophy

Most command-line tools follow the Unix philosophy:

Do one thing and do it well.

grepfilters lineswccounts lines, words, characterssortsorts linesheadshows first lines

The power comes from combining these simple tools.

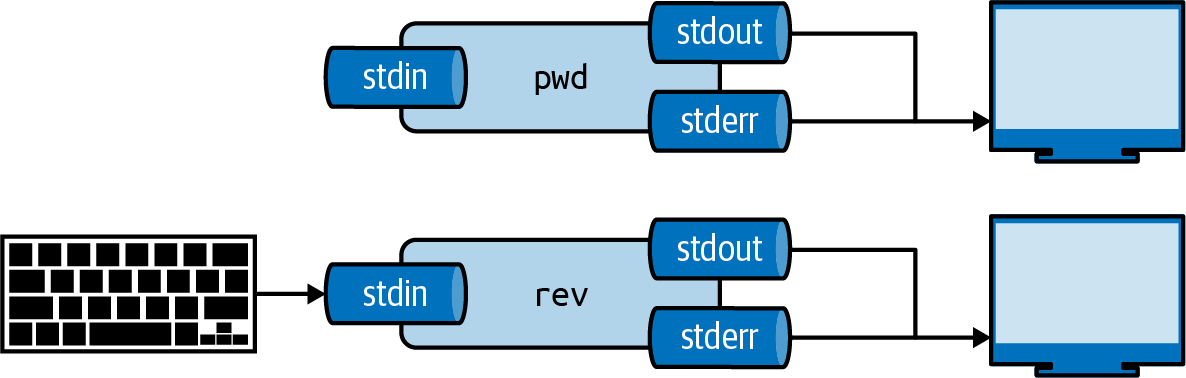

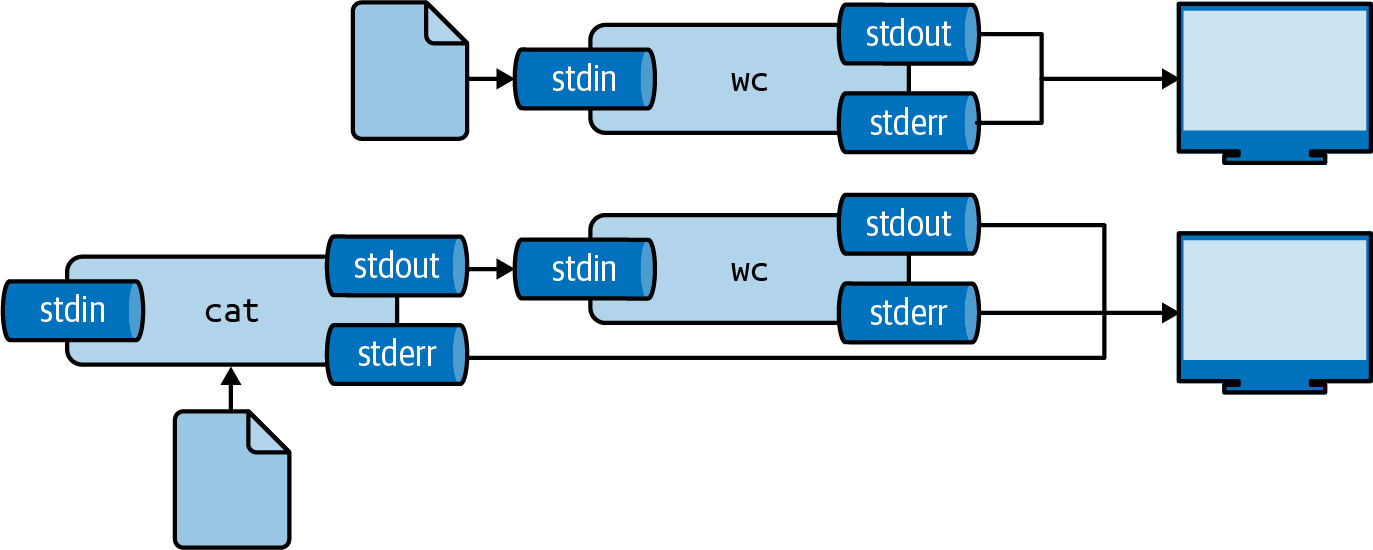

Standard Streams

Every tool has three standard communication streams:

Standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout), and standard error (stderr)

| Stream | Abbreviation | Default |

|---|---|---|

| Standard input | stdin | Keyboard |

| Standard output | stdout | Terminal |

| Standard error | stderr | Terminal |

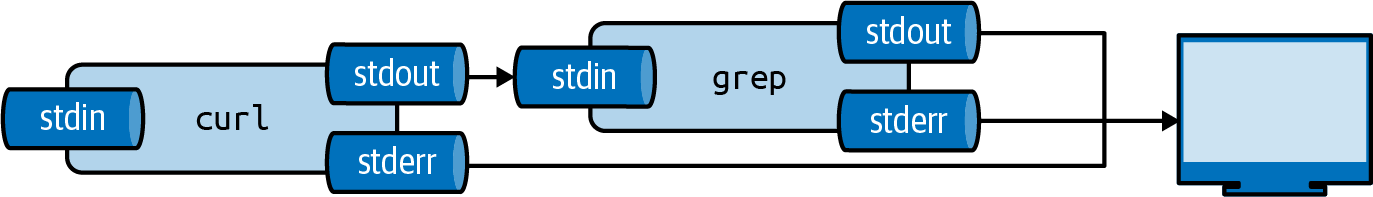

The Pipe Operator

The pipe operator (|) connects stdout of one tool to stdin of another:

Piping output from curl to grep

Chaining Multiple Tools

You can chain as many tools as needed:

This pipeline:

- Downloads Alice in Wonderland

- Filters lines containing ” CHAPTER”

- Counts the number of lines

Think of piping as automated copy and paste.

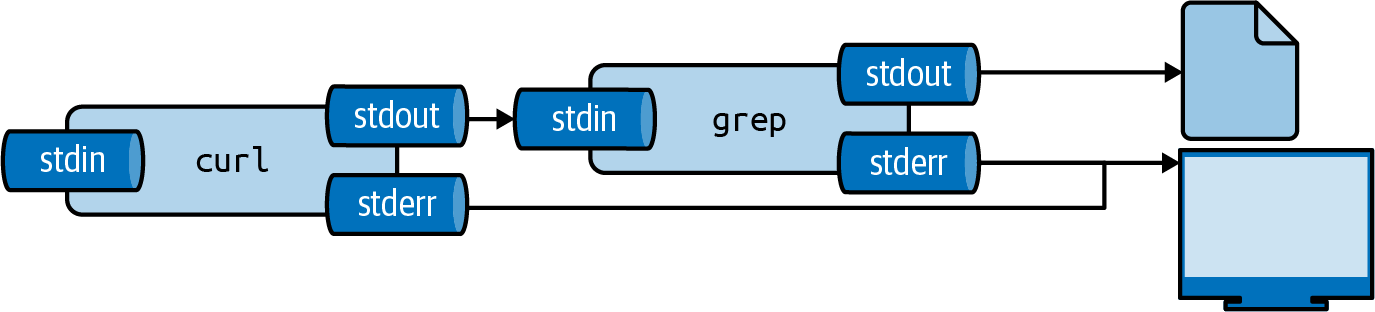

Redirecting Input and Output

Output Redirection

Save output to a file using >:

Redirecting output to a file

- Creates file if it does not exist

- Overwrites file if it exists

- Standard error still goes to terminal

Appending Output

Use >> to append instead of overwrite:

The -n option tells echo not to add a trailing newline.

Input Redirection

Read from a file using <:

Two ways to use file contents as input

Both achieve the same result. The second form avoids starting an extra process.

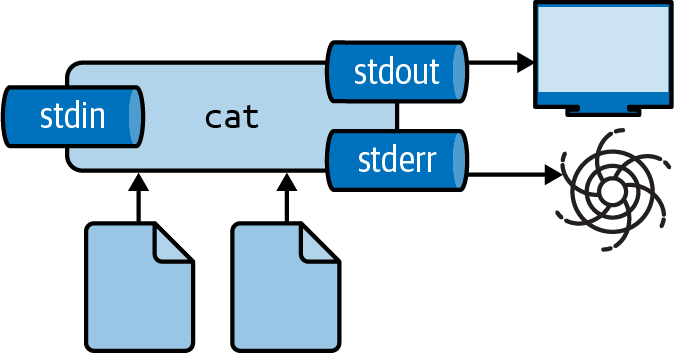

Redirecting Standard Error

Suppress error messages by redirecting stderr to /dev/null:

Redirecting stderr to /dev/null

The 2 refers to standard error (file descriptor 2).

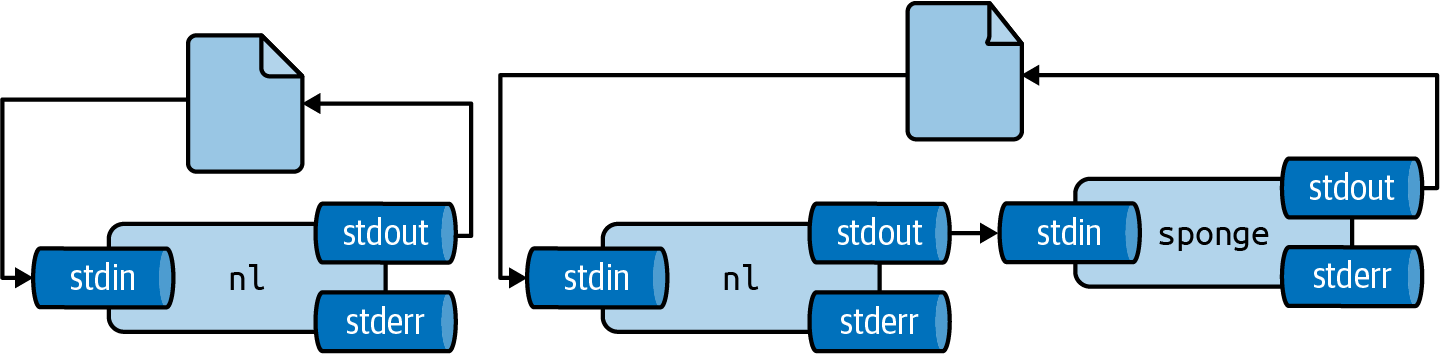

The Sponge Problem

Warning: Do not read from and write to the same file in one command!

The output file is opened (and emptied) before reading starts.

Solutions:

- Write to a different file, then rename

- Use

spongeto absorb all input before writing

sponge soaks up input before writing

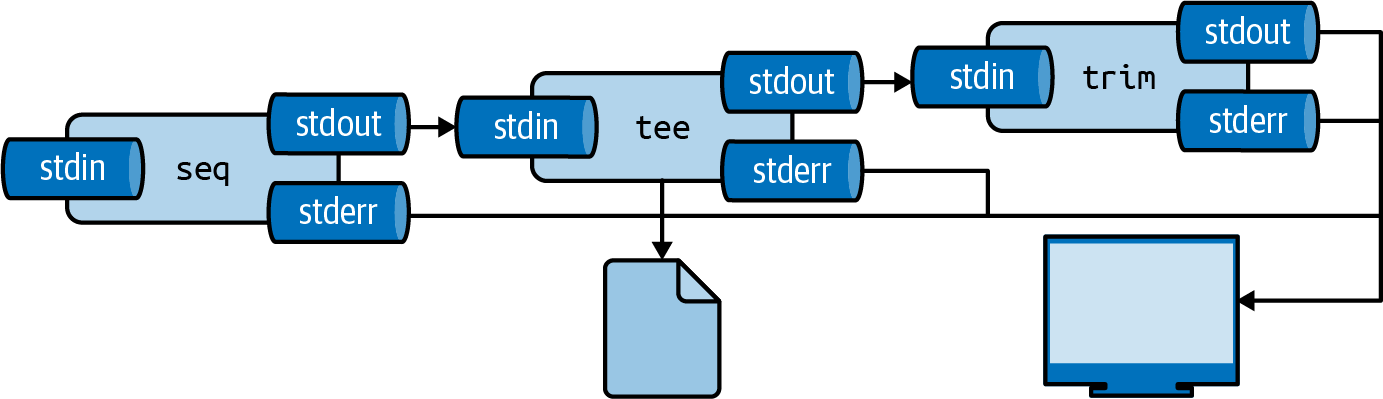

Using tee for Intermediate Output

The tee command writes to both a file and stdout:

tee writes to file while passing data through

Useful for saving intermediate results while continuing a pipeline.

Working with Files and Directories

Listing Directory Contents

Common options:

| Option | Meaning |

|---|---|

-l |

Long format (permissions, size, date) |

-h |

Human-readable sizes |

-F |

Append indicators (/ for directories) |

-a |

Show hidden files |

Creating and Navigating Directories

Moving and Copying Files

Removing Files and Directories

Warning: There is no recycle bin on the command line. Deleted files are gone.

Use the -v (verbose) option to see what is happening:

Getting Help

Manual Pages

The man command displays the manual page for a tool:

Navigation:

- Space or

f: next page b: previous page/pattern: searchq: quit

The –help Option

Many tools support --help:

Some tools use -h instead.

TLDR Pages

For concise, example-focused help, use tldr:

Shows practical examples instead of exhaustive documentation.

Shell Builtins Help

For shell builtins like cd, check the shell manual:

Or use the help command (in bash):

Summary

Key Takeaways

What We Learned

OSEMN Model: Obtain, Scrub, Explore, Model, iNterpret - data science is iterative

Command Line Advantages: Agile, augmenting, scalable, extensible, ubiquitous

Docker Setup: Use

lucascordova/dataengfor a consistent environmentTool Types: Binary executables, shell builtins, scripts, functions, aliases

Pipes and Redirection: Combine simple tools into powerful pipelines

File Management: Navigate, create, copy, move, and remove files

Looking Ahead

Next steps:

- Practice the commands covered today

- Explore the Docker environment

- Complete the command-line exercises

Questions?

References

References

Mason, H. & Wiggins, C. H. (2010). A Taxonomy of Data Science. dataists blog. http://www.dataists.com/2010/09/a-taxonomy-of-data-science

Janssens, J. (2021). Data Science at the Command Line (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media. https://datascienceatthecommandline.com

Raymond, E. S. (2003). The Art of Unix Programming. Addison-Wesley.

Patil, D. J. (2012). Data Jujitsu. O’Reilly Media.

Docker Documentation. https://docs.docker.com

GNU Coreutils Manual. https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/manual