Lecture 05-1: Table Design and Constraints

DATA 503: Fundamentals of Data Engineering

February 9, 2026

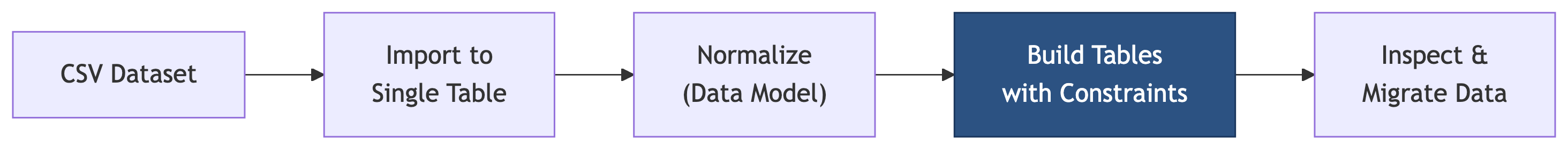

Top-level View 🚁

From Design to Implementation

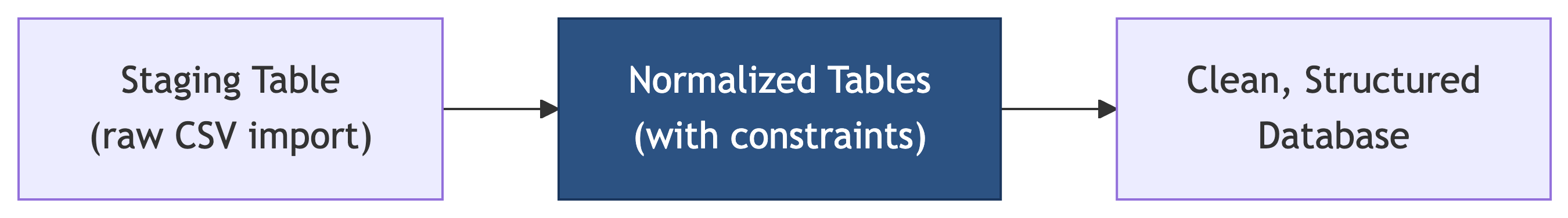

You have learned to import raw data into a single table and design a normalized schema. Now we build the tables that bring that design to life. Think of it as the difference between an architect’s blueprint and actually pouring the concrete.

What Comes Next

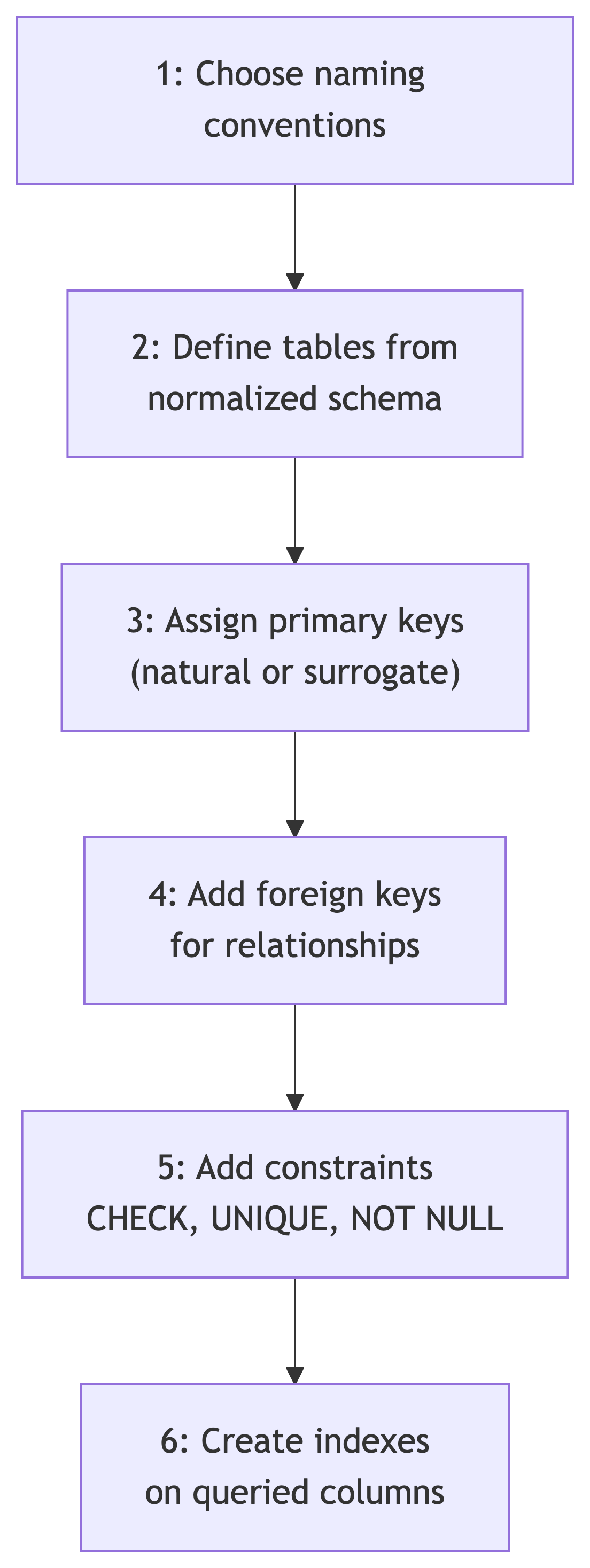

Today we learn the DDL (Data Definition Language) skills to implement your normalized designs:

After today, the next step is migrating data from your staging table into the new structure using INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE.

Setting the Stage with a Running Example: A Music Catalog 🎧

The Scenario

You work for a streaming service that just acquired a catalog of albums from a defunct record distributor. The data arrived as a single CSV file spanning six decades of music, from Fleetwood Mac to Beyonce. Your job is to normalize it and build proper tables.

Here is a sample of what you received:

| catalog_id | artist_name | album_title | release_year | genre | label | duration_min | decade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT-1001 | Fleetwood Mac | Rumours | 1977 | Rock | Warner Bros | 39.4 | 1970s |

| CAT-1002 | Fleetwood Mac | Tango in the Night | 1987 | Rock | Warner Bros | 45.1 | 1980s |

| CAT-1003 | The Beatles | Abbey Road | 1969 | Rock | Apple | 47.4 | 1960s |

| CAT-1004 | The Beatles | Abbey Road | 1969 | Rock | Apple | 47.4 | 1960s |

| CAT-1005 | Led Zepplin | Led Zeppelin IV | 1971 | Rock | Atlantic | 42.5 | 1970 |

| CAT-1006 | Beyonce | Lemonade | 2016 | R&B | Columbia | 45.7 | 2010s |

| CAT-1007 | Beyonce | Renaissance | 2022 | Pop | Columbia | 42.1 | 20s |

| CAT-1008 | Radiohead | OK Computer | 1997 | Alternative | Parlophone | 53.4 | 1990s |

| CAT-1009 | the rolling stones | Sticky Fingers | 1971 | Rock | Rolling Stones | 46.3 | 1970s |

| CAT-1010 | Whitney houston | The Bodyguard | 1992 | Pop | Arista | 56.8 | 1990s |

| CAT-1011 | OutKast | Stankonia | 2000 | Hip-Hop | LaFace | 72.9 | 2000s |

| CAT-1012 | Outkast | Aquemini | 1998 | Hip-Hop | LaFace | 72.6 | 1990s |

If you are already counting problems in that table, good. We will deal with them next time. Today we focus on building the target schema.

The Staging Table

First, we import the CSV into a flat staging table:

CREATE TABLE music_catalog (

catalog_id varchar(20) CONSTRAINT catalog_key PRIMARY KEY,

artist_name varchar(200),

album_title varchar(200),

release_year smallint,

genre varchar(50),

label varchar(100),

duration_min numeric(5,1),

decade varchar(10)

);

COPY music_catalog

FROM '/path/to/album_catalog.csv'

WITH (FORMAT CSV, HEADER, DELIMITER ',');This staging table holds raw, denormalized data. It is a holding pen, not a home.

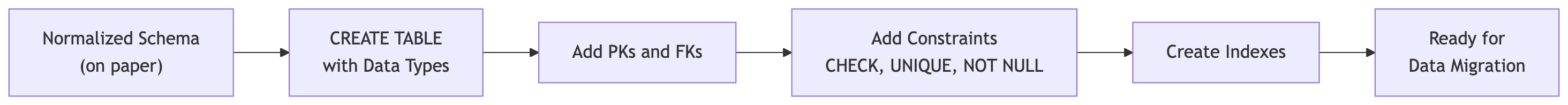

Identifying Entities

The staging table mixes artist data with album data in every row. Normalization separates them into distinct tables with relationships. Looking at the data, we can identify distinct entities:

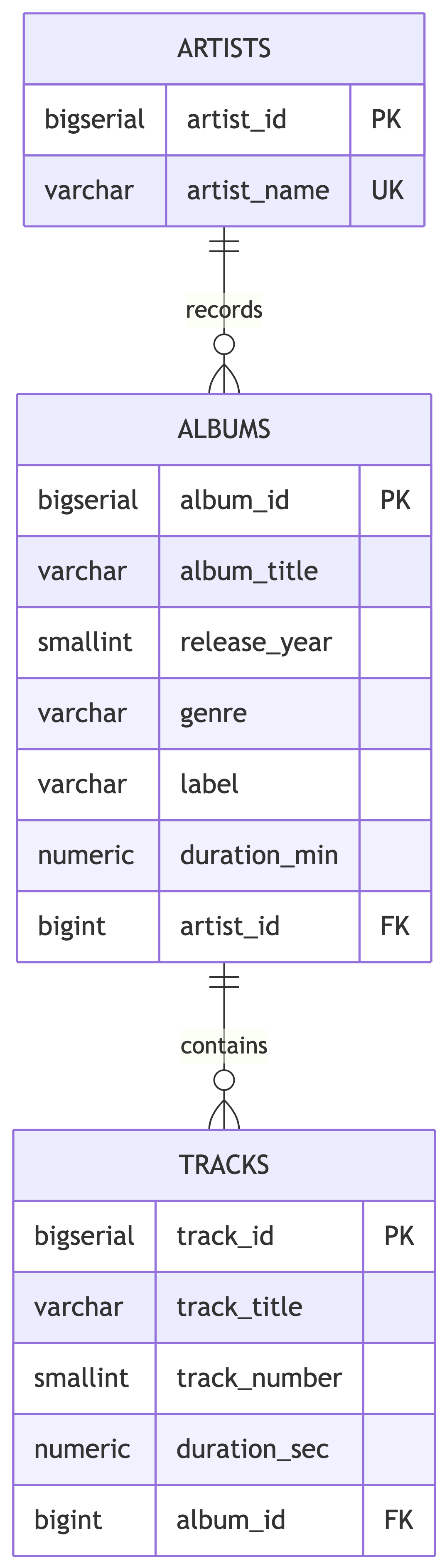

The Normalized Target

Our goal is three tables:

artists– one row per unique artistalbums– one row per unique album, linked to an artisttracks– one row per track, linked to an album

The staging table gets us to artists and albums. Track data would come from a separate source, but we will build the table structure anyway. In the real world, schemas are built for the data you expect, not just the data you have.

Now let us learn the DDL skills to build these tables properly.

Naming Conventions

Why Naming Matters

Good naming conventions make your database self-documenting. A well-named schema tells you what it contains without reading a single comment.

Bad naming leads to:

- Confusion when writing queries

- Bugs from misremembering column names

- Onboarding headaches for new team members

- Passive-aggressive comments in code reviews

PostgreSQL Naming Rules

PostgreSQL has specific rules for identifiers (table and column names):

- Can contain letters, digits, and underscores

- Must begin with a letter or underscore

- Are case-insensitive by default (folded to lowercase)

- Maximum length of 63 characters

PostgreSQL treats your shouting the same as your whispering.

The Case Sensitivity Trap

PostgreSQL folds unquoted identifiers to lowercase. If you use double quotes, the name becomes case-sensitive:

Warning

Avoid double-quoted identifiers. They create maintenance headaches because every query must use the exact casing with quotes. You will curse your past self at 2 AM.

Best Practices for Naming

| Convention | Example | Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Use snake_case | release_year |

releaseYear, ReleaseYear |

| Be descriptive | artist_name |

art_nm |

| Use plurals for tables | artists, albums |

artist, album |

| Include context | duration_min |

data_column_7 |

| Prefix dates | report_2026_01_15 |

15_01_2026_report |

Naming: Tables vs Columns

Tables represent collections of entities. Use plural nouns:

artists(notartist)albums(notalbum)tracks(nottrack)

Columns represent attributes. Use singular, descriptive names:

artist_name(notartist_names)release_year(notyears_released)duration_min(notdur)

For many-to-many relationships, combine both table names:

artist_genresalbum_tracksplaylist_songs

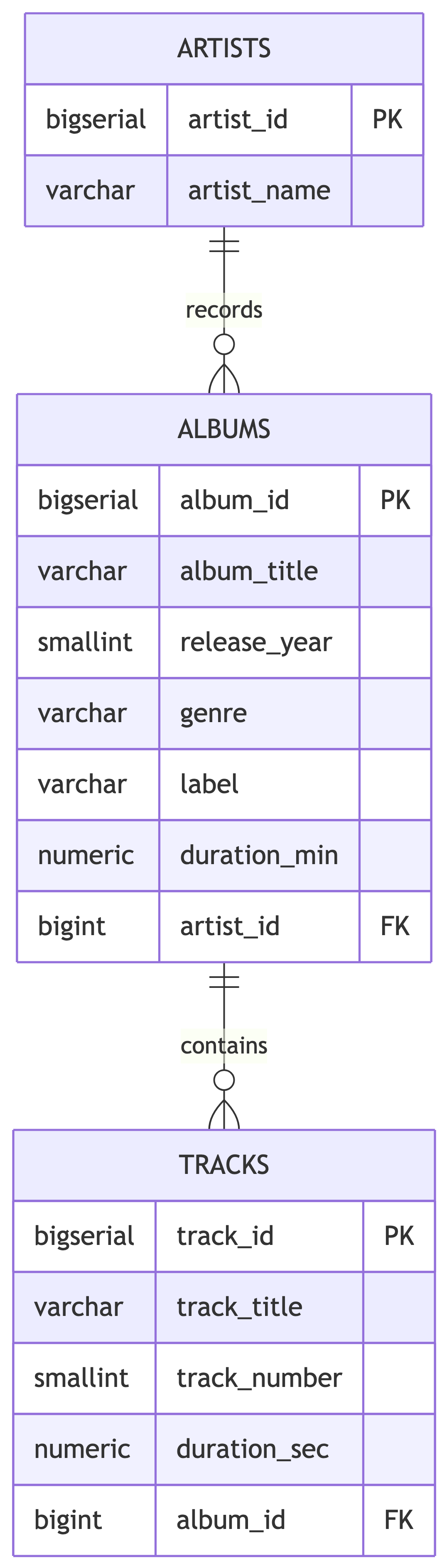

Primary Keys

Recap: What Is a Primary Key?

A primary key uniquely identifies each row in a table. It provides:

- Uniqueness: No two rows share the same key value

- Non-nullability: The key value cannot be NULL

- Identity: A reliable way to reference a specific row

Every table in a well-designed database should have a primary key.

Two Approaches to Primary Keys

Natural Keys

A natural key uses data that already exists and naturally identifies the entity.

Here license_id is a real-world identifier. Each person has exactly one, and it is unique. In theory. In practice, natural keys have a habit of being less unique than you were promised.

Natural Keys: Testing Uniqueness

Let us see what happens when we violate the primary key:

The second INSERT fails:

ERROR: duplicate key value violates unique constraint "license_key"

DETAIL: Key (license_id)=(T229901) already exists.The database enforces uniqueness automatically. It is polite about it, but firm.

Natural Keys: Music Catalog Example

Could we use a natural key for our albums table? The catalog_id from the staging data is a candidate:

This works if every album has a unique catalog code. But what if the same album is reissued with a new code? Or acquired from a different distributor with a different code? Natural keys work until the real world gets creative.

Composite Natural Keys

Sometimes no single column is unique, but a combination is:

A student can only have one attendance record per day. Neither student_id nor school_day is unique alone, but together they form a unique identifier.

Composite Keys: Testing Uniqueness

INSERT INTO natural_key_composite_example (student_id, school_day, present)

VALUES(775, '1/22/2017', 'Y');

INSERT INTO natural_key_composite_example (student_id, school_day, present)

VALUES(775, '1/23/2017', 'Y'); -- OK: different day

INSERT INTO natural_key_composite_example (student_id, school_day, present)

VALUES(775, '1/23/2017', 'N'); -- FAILS: same student + dayERROR: duplicate key value violates unique constraint "student_key"

DETAIL: Key (student_id, school_day)=(775, 2017-01-23) already exists.Surrogate Keys

A surrogate key is a system-generated value with no real-world meaning:

PostgreSQL’s serial types auto-generate incrementing integers:

| Type | Range |

|---|---|

smallserial |

1 to 32,767 |

serial |

1 to 2,147,483,647 |

bigserial |

1 to 9.2 quintillion |

Surrogate Keys: Auto-Increment in Action

artist_id | artist_name

-----------+---------------

1 | Fleetwood Mac

2 | The Beatles

3 | BeyonceNotice we never specified artist_id. PostgreSQL generated it automatically. One less thing to argue about in a design meeting.

Natural vs Surrogate: When to Use Which

| Factor | Natural Key | Surrogate Key |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Has real-world meaning | Meaningless identifier |

| Stability | Can change (email, name) | Never changes |

| Size | Varies (could be long) | Fixed, compact |

| Performance | Depends on data type | Fast (integer) |

| Universality | Not always available | Always available |

Tip

Practical guidance: Use surrogate keys (serial/bigserial) as primary keys for most tables. If a natural key exists and is truly stable (ISBN, SSN), consider it. When in doubt, surrogate wins. Nobody has ever been fired for using a serial primary key.

Two Syntax Styles for PRIMARY KEY

You can declare a primary key inline or as a table constraint:

Best for single-column keys.

Foreign Keys

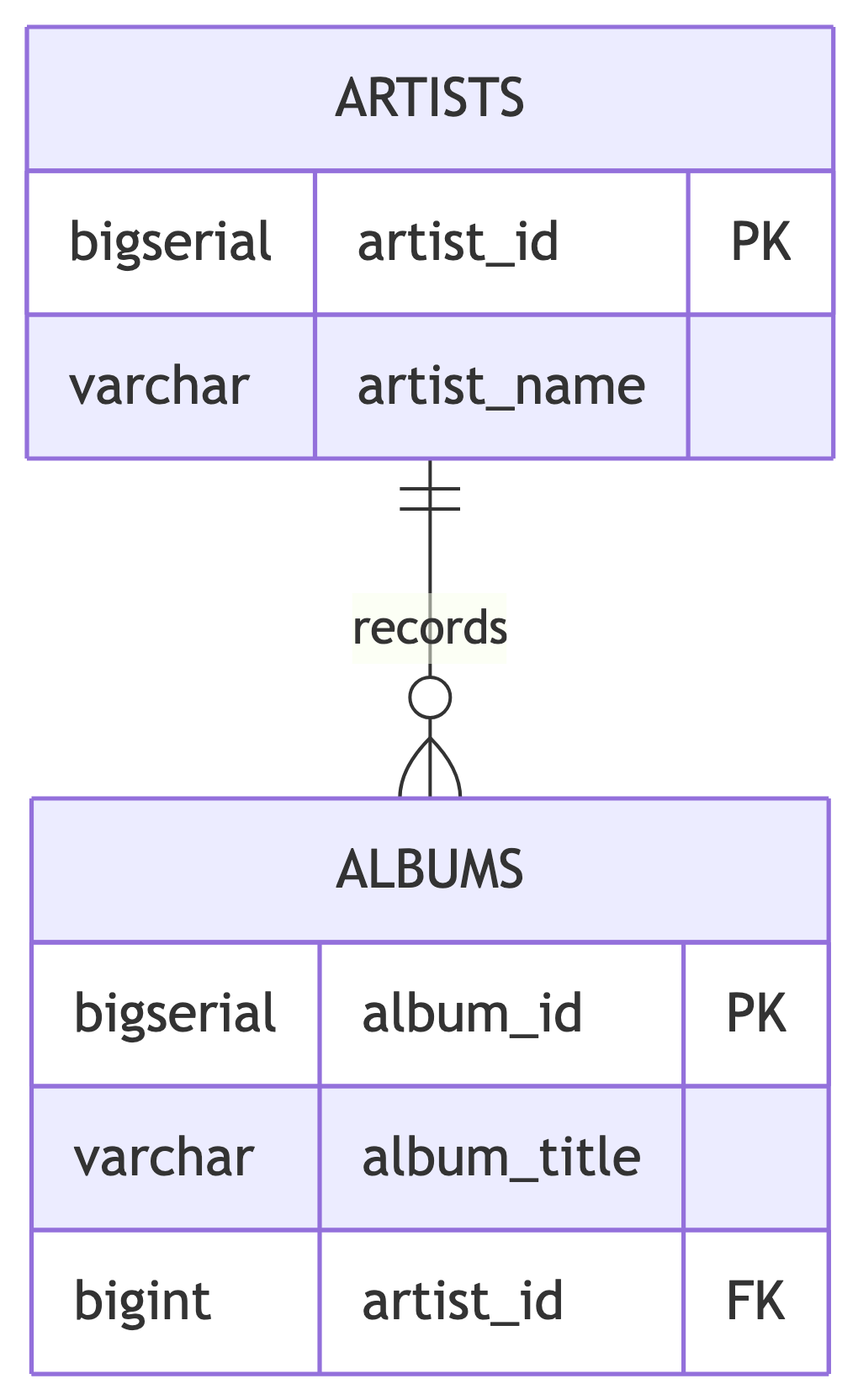

Connecting Tables with Foreign Keys

A foreign key is a column in one table that references the primary key of another table. It enforces referential integrity: you cannot reference a row that does not exist.

Creating Foreign Key Relationships

CREATE TABLE artists (

artist_id bigserial,

artist_name varchar(200) NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT artist_key PRIMARY KEY (artist_id)

);

CREATE TABLE albums (

album_id bigserial,

album_title varchar(200) NOT NULL,

release_year smallint,

artist_id bigint REFERENCES artists (artist_id),

CONSTRAINT album_key PRIMARY KEY (album_id)

);The REFERENCES keyword creates the foreign key relationship. It is essentially a contract: “I promise this value exists over there, and I would like the database to hold me to it.”

Foreign Keys: Enforcing Referential Integrity

ERROR: insert or update on table "albums" violates foreign key

constraint "albums_artist_id_fkey"

DETAIL: Key (artist_id)=(999) is not present in table "artists".What Happens When You Delete a Parent Row?

By default, PostgreSQL prevents deleting a row from the parent table if child rows reference it. This protects data integrity but can be inconvenient.

ON DELETE CASCADE tells PostgreSQL to automatically delete child rows when the parent is deleted:

Delete an album, and all its tracks vanish with it. This is appropriate when child rows have no meaning without the parent.

ON DELETE Options

| Option | Behavior |

|---|---|

RESTRICT (default) |

Prevent deletion if children exist |

CASCADE |

Delete children automatically |

SET NULL |

Set foreign key to NULL in children |

SET DEFAULT |

Set foreign key to default value in children |

Warning

Use CASCADE carefully. Deleting one artist could cascade through albums and tracks, removing far more data than intended. CASCADE is the database equivalent of pulling a loose thread on a sweater.

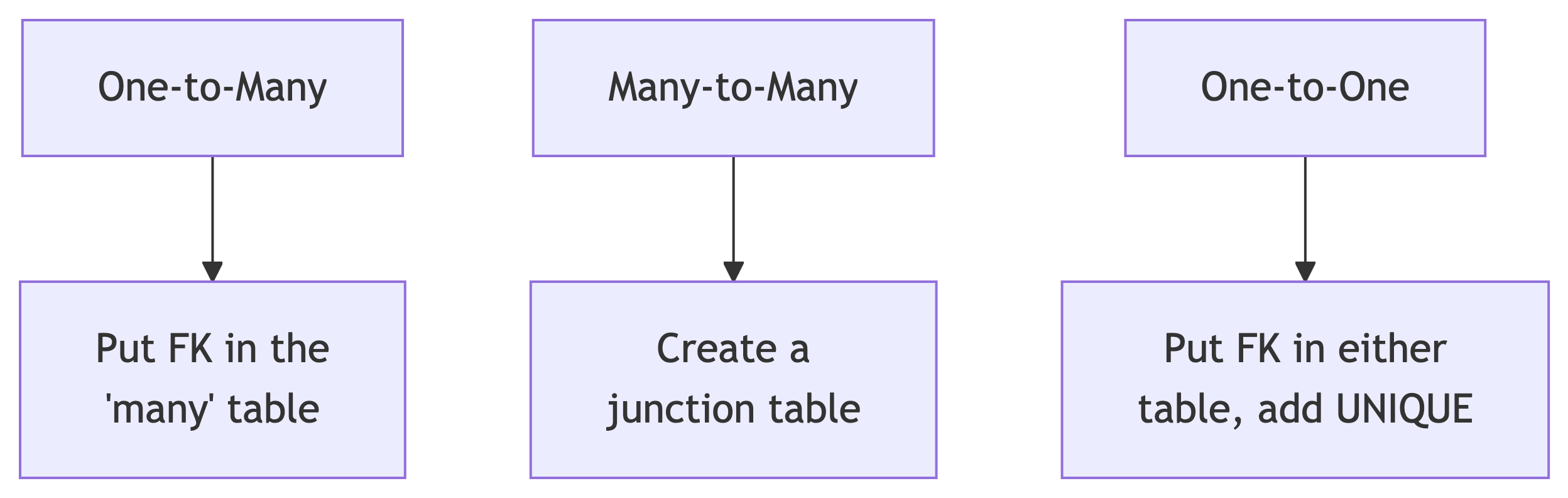

Foreign Key Design Patterns

One-to-Many: An artist has many albums. Put artist_id in the albums table.

Many-to-Many: Artists perform in many genres; genres have many artists. Create artist_genres with FKs to both.

One-to-One: An artist has one biography. Put artist_id in biographies with a UNIQUE constraint.

CHECK Constraints

Validating Data with CHECK

A CHECK constraint ensures that column values meet a logical condition. If the condition evaluates to false, the row is rejected.

CREATE TABLE albums (

album_id bigserial,

album_title varchar(200) NOT NULL,

release_year smallint,

genre varchar(50),

duration_min numeric(5,1),

artist_id bigint REFERENCES artists (artist_id),

CONSTRAINT album_key PRIMARY KEY (album_id),

CONSTRAINT check_year_range

CHECK (release_year BETWEEN 1900 AND 2100),

CONSTRAINT check_duration_positive

CHECK (duration_min > 0)

);CHECK: Practical Examples

CHECK constraints can enforce a wide variety of business rules:

-- Genre must be from a known list

CONSTRAINT check_genre

CHECK (genre IN ('Rock', 'Pop', 'Hip-Hop', 'R&B',

'Country', 'Electronic', 'Alternative', 'Jazz'))

-- Release year must be reasonable

CONSTRAINT check_year_range

CHECK (release_year BETWEEN 1900 AND 2100)

-- Track number must be positive

CONSTRAINT check_track_positive

CHECK (track_number > 0)

-- Duration must be within reason

CONSTRAINT check_duration

CHECK (duration_sec BETWEEN 1 AND 7200)When to Use CHECK Constraints

| Scenario | Example |

|---|---|

| Enumerated values | genre IN ('Rock', 'Pop', 'Jazz') |

| Numeric ranges | release_year BETWEEN 1900 AND 2100 |

| Comparison between columns | end_date > start_date |

| Non-negative values | duration_min > 0 |

| String patterns | email LIKE '%@%.%' |

Tip

CHECK constraints catch bad data at the database level, regardless of which application inserts it. This is your last line of defense. Applications come and go, but the database remembers.

UNIQUE Constraints

Enforcing Uniqueness Beyond the Primary Key

A UNIQUE constraint ensures no duplicate values exist in a column (or combination of columns), separate from the primary key.

This prevents inserting two artists with the same name. Whether that is desirable depends on whether you believe there is only one “John Williams” in the music industry. (There are at least two famous ones.)

UNIQUE: Testing the Constraint

ERROR: duplicate key value violates unique constraint "artist_name_unique"

DETAIL: Key (artist_name)=(Beyonce) already exists.Composite UNIQUE Constraints

Sometimes uniqueness requires multiple columns. An album title is not unique by itself (many artists have a self-titled album), but the combination of artist and title should be:

Now two different artists can both have “Greatest Hits,” but the same artist cannot have two albums with the same title.

UNIQUE vs PRIMARY KEY

| Feature | PRIMARY KEY | UNIQUE |

|---|---|---|

| Uniqueness | Yes | Yes |

| Allows NULL | No | Yes (one NULL per column) |

| Per table | Only one | Multiple allowed |

| Creates index | Yes | Yes |

A table has one primary key but can have many UNIQUE constraints. Use UNIQUE for candidate keys that are not the primary key.

NOT NULL Constraints

Requiring Values with NOT NULL

NOT NULL prevents a column from containing NULL values. This is essential for columns that must always have data:

Any INSERT that omits artist_name (or sets it to NULL) will fail. An artist without a name is not an artist. It is a mystery.

When to Use NOT NULL

Apply NOT NULL to columns where missing data would be meaningless or harmful:

| Always NOT NULL | Often Nullable |

|---|---|

artist_name |

label (indie releases) |

album_title |

genre (might be ambiguous) |

track_title |

duration_min (might be unknown) |

| Foreign keys (usually) | release_year (might be disputed) |

track_number |

Notes, descriptions |

Tip

Default to NOT NULL and only allow NULLs when there is a legitimate reason for missing data. This catches bugs early. Future you will appreciate the strictness, even if present you finds it annoying.

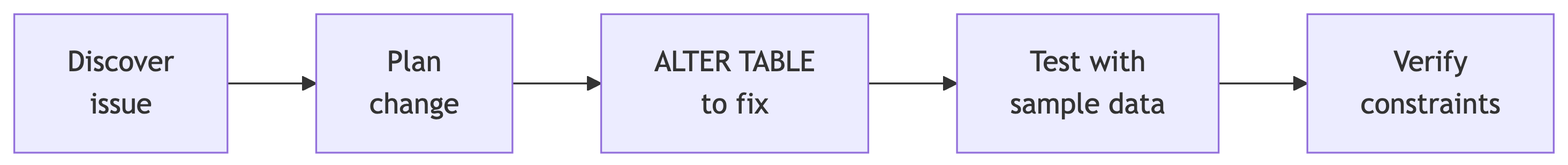

Modifying Tables with ALTER TABLE

Adding and Removing Constraints

You do not always get the design right on the first try. Nobody does. If you did, you would be suspicious. ALTER TABLE lets you modify constraints after creation:

ALTER TABLE: NOT NULL

NOT NULL constraints use a different syntax because they are column properties, not named constraints:

Common ALTER TABLE Operations

| Operation | Syntax |

|---|---|

| Drop constraint | ALTER TABLE t DROP CONSTRAINT c; |

| Add constraint | ALTER TABLE t ADD CONSTRAINT c ...; |

| Drop NOT NULL | ALTER TABLE t ALTER COLUMN col DROP NOT NULL; |

| Set NOT NULL | ALTER TABLE t ALTER COLUMN col SET NOT NULL; |

| Add column | ALTER TABLE t ADD COLUMN col type; |

| Drop column | ALTER TABLE t DROP COLUMN col; |

| Rename column | ALTER TABLE t RENAME COLUMN old TO new; |

| Rename table | ALTER TABLE t RENAME TO new_name; |

ALTER TABLE in Practice

A common workflow when evolving a database:

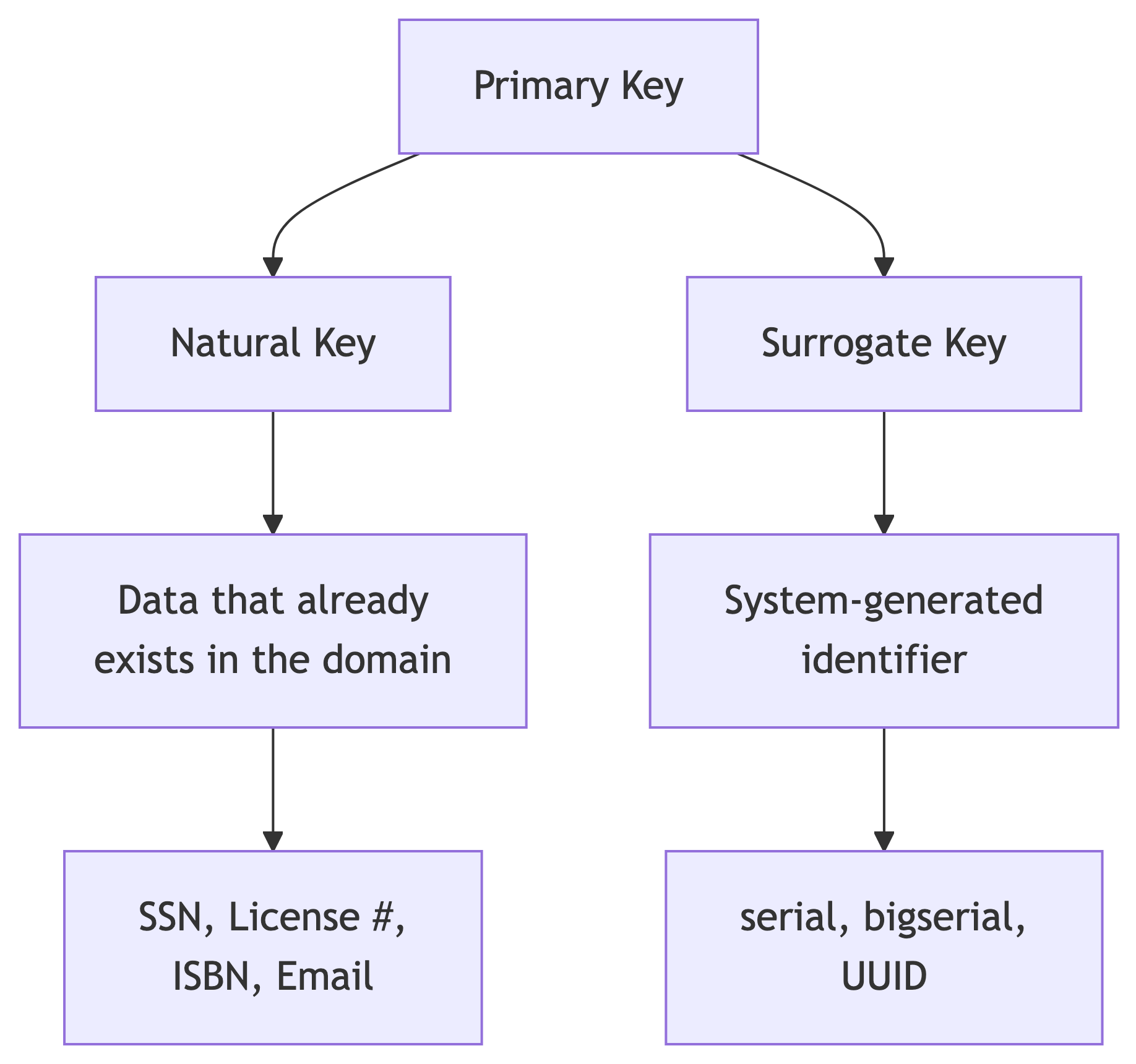

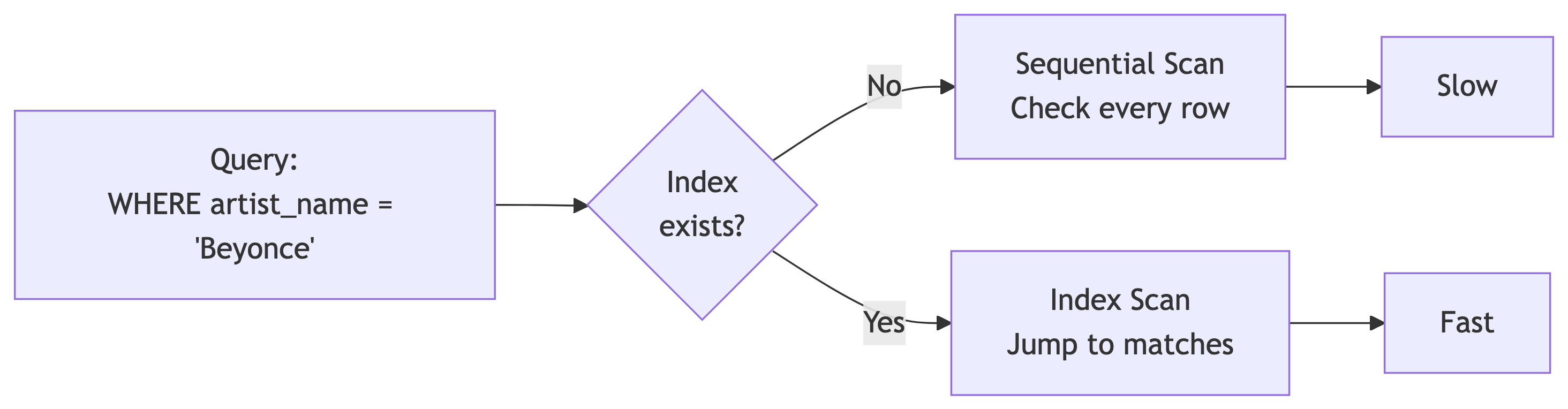

Speeding Things Up: Indexes

What Is an Index?

An index is a data structure that speeds up data retrieval at the cost of additional storage and slower writes.

Think of it like the index at the back of a textbook: instead of reading every page to find “normalization,” you look it up in the index and jump directly to the right page. Databases without indexes are just very patient.

Without an Index: Sequential Scan

PostgreSQL reads every single row in the table:

Seq Scan on music_catalog

(cost=0.00..20730.68 rows=12 width=46)

(actual time=0.055..289.426 rows=8 loops=1)

Filter: ((artist_name)::text = 'Beyonce'::text)

Rows Removed by Filter: 601

Planning time: 0.617 ms

Execution time: 289.838 msOn a large catalog, scanning every row adds up. Now imagine a thousand users searching simultaneously.

Creating an Index

These build B-tree indexes (the default) on frequently queried columns.

When to Create Indexes

| Create Index When | Skip Index When |

|---|---|

| Column used in WHERE clauses | Table is small (< 1000 rows) |

| Column used in JOIN conditions | Column has few distinct values |

| Column used in ORDER BY | Table has heavy INSERT/UPDATE load |

| Foreign key columns | You rarely query the column |

Tip

PostgreSQL automatically creates indexes on PRIMARY KEY and UNIQUE columns. You only need to manually create indexes on other frequently queried columns.

EXPLAIN ANALYZE: Your Performance Detective

EXPLAIN ANALYZE shows you exactly how PostgreSQL executes a query:

Key things to look for:

- Seq Scan: Reading every row (potentially slow)

- Index Scan / Bitmap Index Scan: Using an index (fast)

- Execution time: Total query time in milliseconds

- Rows Removed by Filter: How many rows were checked but not returned

Managing Indexes

Indexes are not free:

- They consume disk space

- They slow down INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE operations

- Too many indexes can hurt overall performance

Balance is key. Index the columns you query most. Indexing everything is like highlighting every word in a textbook. At that point, nothing is highlighted.

Building the Music Catalog Schema 🏗️

Putting It All Together

Now we apply everything we have learned to build the normalized music catalog tables. The staging table holds the raw import. These tables hold the clean, structured data.

The Artists Table

Key decisions:

- Surrogate key (

bigserial) because artist names can change or have variations artist_nameis NOT NULL and UNIQUE (every artist needs a name, and we do not want duplicates after cleaning)

The Albums Table

CREATE TABLE albums (

album_id bigserial,

album_title varchar(200) NOT NULL,

release_year smallint,

genre varchar(50),

label varchar(100),

duration_min numeric(5,1),

artist_id bigint NOT NULL REFERENCES artists (artist_id),

CONSTRAINT album_key PRIMARY KEY (album_id),

CONSTRAINT check_year_range

CHECK (release_year BETWEEN 1900 AND 2100),

CONSTRAINT check_duration_positive

CHECK (duration_min > 0),

CONSTRAINT album_artist_unique

UNIQUE (album_title, artist_id)

);Key decisions:

artist_idis NOT NULL (every album must have an artist)- CHECK on year range catches obvious errors

- Composite UNIQUE on title + artist prevents duplicate albums per artist

genreis nullable (some albums defy classification, and our staging data has NULLs)

The Tracks Table

CREATE TABLE tracks (

track_id bigserial,

track_title varchar(200) NOT NULL,

track_number smallint NOT NULL,

duration_sec numeric(6,1),

album_id bigint NOT NULL REFERENCES albums (album_id),

CONSTRAINT track_key PRIMARY KEY (track_id),

CONSTRAINT check_track_number

CHECK (track_number > 0),

CONSTRAINT check_track_duration

CHECK (duration_sec > 0),

CONSTRAINT track_album_unique

UNIQUE (track_number, album_id)

);Key decisions:

album_idis NOT NULL (every track belongs to an album)- Composite UNIQUE on track_number + album prevents duplicate track numbers within an album

duration_secis nullable (metadata is not always complete)

Indexes for Common Queries

-- Speed up lookups by artist (for album listings)

CREATE INDEX idx_albums_artist ON albums (artist_id);

-- Speed up lookups by album (for track listings)

CREATE INDEX idx_tracks_album ON tracks (album_id);

-- Speed up genre-based browsing

CREATE INDEX idx_albums_genre ON albums (genre);

-- Speed up searches by release year

CREATE INDEX idx_albums_year ON albums (release_year);Foreign key columns and frequently filtered columns are good index candidates.

The Complete Schema

Three tables, proper constraints, indexes on the right columns. The staging table holds 609 rows of messy data. These tables are ready to hold the clean version.

Constraints Summary

| Constraint | Purpose | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| PRIMARY KEY | Unique row identifier | CONSTRAINT name PRIMARY KEY (col) |

| FOREIGN KEY | Referential integrity | col type REFERENCES table (col) |

| CHECK | Value validation | CONSTRAINT name CHECK (expr) |

| UNIQUE | No duplicates | CONSTRAINT name UNIQUE (col) |

| NOT NULL | Requires a value | col type NOT NULL |

Next Up! 🚀

What Is Next

Now that you can build tables with proper constraints, the next step is inspecting and migrating data from the staging table into the new structure.

Next time we will:

- Audit the staging data for quality issues (spoiler: there are many)

- Fix inconsistencies with UPDATE

- Migrate data into our normalized tables using INSERT INTO … SELECT

- Wrap it all in transactions for safety

References 📚

Sources

DeBarros, A. (2022). Practical SQL: A Beginner’s Guide to Storytelling with Data (2nd ed.). No Starch Press. Chapter 7: Table Design That Works for You.

PostgreSQL Documentation. “CREATE TABLE.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/sql-createtable.html

PostgreSQL Documentation. “Indexes.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/indexes.html

PostgreSQL Documentation. “Constraints.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/ddl-constraints.html