Lecture 05-2: Inspecting and Modifying Data

DATA 503: Fundamentals of Data Engineering

February 9, 2026

Overview 🚁

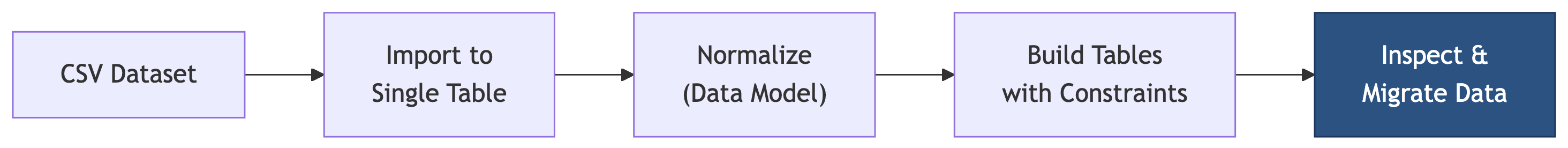

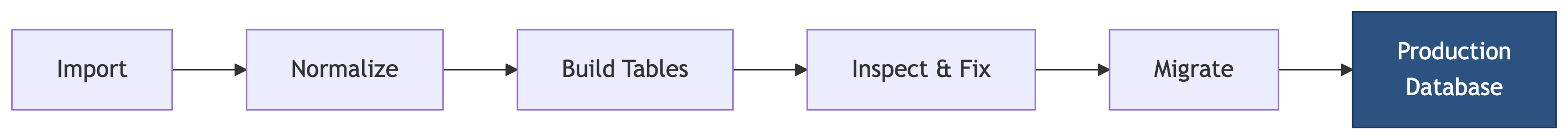

Where We Are in the Pipeline

We built the tables. We added constraints. Now comes the part where we actually move the data from the staging table into the normalized schema without breaking anything. No pressure.

The Data Migration Challenge

Let’s say you have a staging table (music_catalog) full of raw CSV data and a set of normalized tables (artists, albums, tracks) waiting to receive it. The problem is that raw data is rarely clean enough to insert directly.

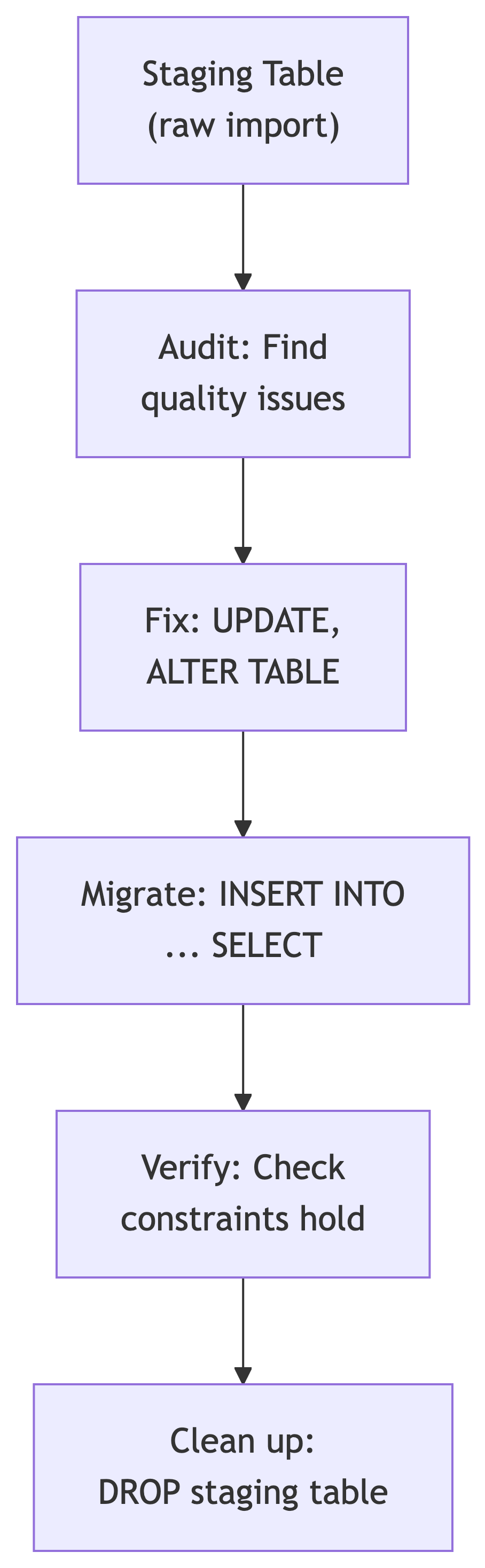

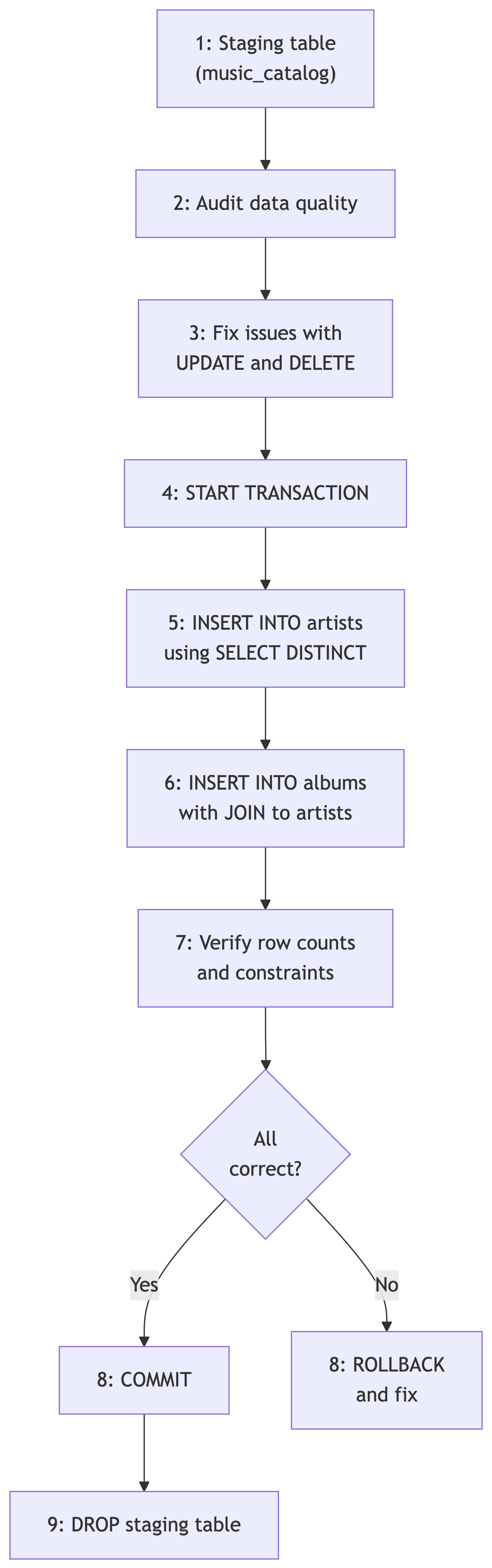

The workflow:

What You Will Learn Today

The DML (Data Manipulation Language) toolkit:

| Statement | Purpose |

|---|---|

UPDATE |

Change existing values |

DELETE |

Remove rows |

ALTER TABLE |

Modify table structure |

INSERT INTO ... SELECT |

Copy data between tables |

START TRANSACTION |

Begin a safe modification block |

COMMIT |

Save changes permanently |

ROLLBACK |

Undo everything since the last transaction start |

These are the verbs of data engineering. SELECT asks questions. These statements change answers.

Auditing Data Quality Process 🧪

The Inspection Mindset

Before modifying anything, inspect the data. Every experienced data engineer has a horror story about an UPDATE that ran without a WHERE clause. Do not become a horror story.

Questions to ask before any migration:

- How many rows do I have?

- Are there NULLs where there should not be?

- Are values consistent? (Same entity, different spellings?)

- Are there duplicates?

- Do the data types match the target schema?

Recall: The Music Catalog Staging Table

Last time, we imported a CSV of album data from a defunct record distributor and built our normalized target tables (artists, albums, tracks). The staging table looks like this:

Six decades of music. Also six decades of data entry by people who apparently had strong opinions about capitalization.

Audit Step 1: How Many Rows?

Always start with the basics:

count

-------

609This tells you the scale of what you are working with. A table with 50 rows and a table with 5 million rows require different strategies. One you can eyeball. The other, you cannot.

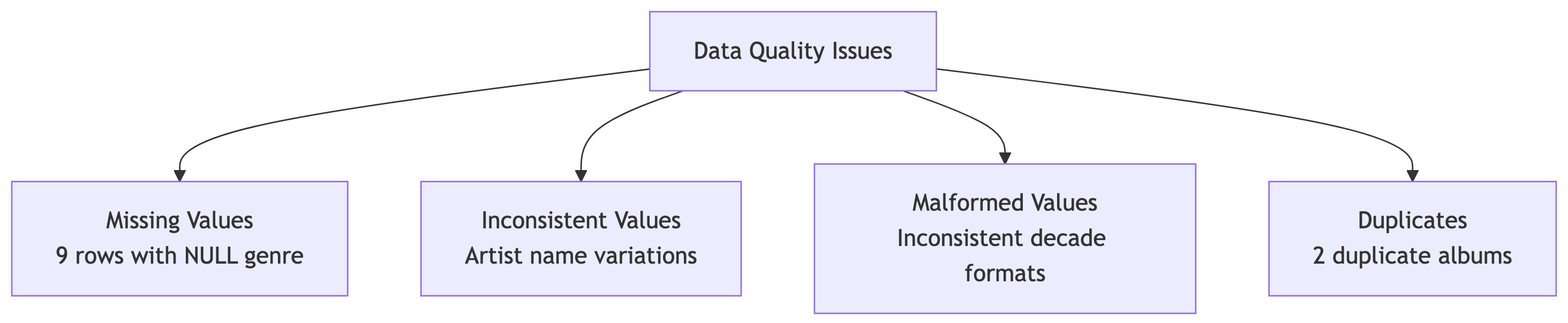

Audit Step 2: Find Duplicate Albums

artist_name album_title album_count

----------------- ----------------------- -----------

Radiohead OK Computer 2

The Beatles Abbey Road 2GROUP BY with HAVING count(*) > 1 is your duplicate detector. Same artist, same album, appearing twice. Could be a reissue. Could be a data entry mistake. Usually the latter.

Audit Step 3: Find NULL Values

genre genre_count

------------- -----------

Alternative 87

Country 34

Electronic 45

Hip-Hop 62

Pop 128

R&B 41

Rock 203

9Nine rows have no genre. That blank line at the bottom is NULL. NULL is not nothing. NULL is “I do not know,” which in a database is significantly worse than nothing.

Audit Step 3b: Investigate the NULLs

IS NULL is the only way to check for NULL. Using = NULL will not work because NULL is not equal to anything, including itself. This is one of those things that makes perfect logical sense and no intuitive sense whatsoever.

Audit Step 4: Inconsistent Names

artist_name name_count

--------------------------- ----------

Led Zeppelin 3

Led Zepplin 1

Outkast 2

OutKast 1

the rolling stones 1

The Rolling Stones 4

Whitney Houston 3

Whitney houston 1Eight entries for what should be four artists. Typos, inconsistent casing, and missing “The” prefixes. In a normalized database, each artist would be one row. In this staging table, each variation is a separate identity crisis.

Audit Step 5: Malformed Decade Values

decade decade_count

---------- ------------

1970 42

1970s 58

1980s 89

1990s 104

2000s 97

2010s 78

20s 12

2020s 29Three problems: “1970” should be “1970s”, “20s” should be “2020s”, and the two 1970s variants need merging. Whoever entered this data was consistent about 60% of the time, which is the worst kind of consistent.

Audit Step 5b: Check Release Years Against Decades

decade earliest latest

---------- -------- ------

1970 1970 1979

1970s 1970 1979

1980s 1980 1989

1990s 1990 1999

2000s 2000 2009

2010s 2010 2019

20s 2020 2024

2020s 2020 2025At least the years match the decades. Small mercies.

Data Quality Audit Summary

Our audit revealed three categories of problems:

Now we fix them. But first, a word about safety.

The Golden Rule of Data Modification 📜

Backup Before You Modify!

Always create a backup before running UPDATE or DELETE on production data.

This is not optional. This is not paranoia. This is professionalism. The difference between a junior and senior data engineer is not skill. It is the number of times they have been burned by a missing backup.

Creating a Backup Table

CREATE TABLE ... AS SELECT copies both structure and data. Verify the backup:

original backup

-------- ------

609 609Same count. You can proceed with slightly less anxiety.

The Safety Column Pattern

Before modifying a column, copy it first:

Now artist_name_copy preserves the original values. If your UPDATE goes sideways, you can restore from the copy without touching the backup table. Belt and suspenders.

Changing Structure 📦

ALTER TABLE: Modifying Table Structure

ALTER TABLE changes the shape of a table without destroying its data:

| Operation | Syntax |

|---|---|

| Add column | ALTER TABLE t ADD COLUMN col type; |

| Drop column | ALTER TABLE t DROP COLUMN col; |

| Change type | ALTER TABLE t ALTER COLUMN col SET DATA TYPE type; |

| Set NOT NULL | ALTER TABLE t ALTER COLUMN col SET NOT NULL; |

| Drop NOT NULL | ALTER TABLE t ALTER COLUMN col DROP NOT NULL; |

Adding Columns for Data Cleaning

A common pattern: add a new “clean” column alongside the original dirty one.

Now you can clean artist_standard without losing the original artist_name values. When you are satisfied the cleaning is correct, you can drop the original. Or keep both. Data engineers who keep both sleep better.

Updating and Fixing Data 🧰

The UPDATE Statement

UPDATE changes existing values in a table:

Warning

An UPDATE without a WHERE clause modifies every row in the table. PostgreSQL will not ask “are you sure?” It will simply do it. Immediately. With enthusiasm.

Fixing Missing Genres

We found nine rows with NULL genres. After researching the albums, we can fill them in:

Each UPDATE returns UPDATE 1 (or UPDATE 3 for the IN clause), confirming the exact number of rows modified. If it says UPDATE 0, your WHERE clause matched nothing. If it says UPDATE 609, you forgot the WHERE clause. Both are worth investigating.

Restoring from a Safety Column

If your UPDATE was wrong, restore from the copy:

Option 2 uses UPDATE ... FROM, which joins two tables during the update. This is PostgreSQL-specific syntax and extremely useful for data migration work.

Standardizing Artist Names

Remember the inconsistent spellings? Fix them with pattern matching and exact matches:

-- Fix the typo

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'Led Zeppelin'

WHERE artist_name LIKE 'Led Zep%';

-- Fix casing inconsistencies

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'OutKast'

WHERE lower(artist_name) = 'outkast';

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'The Rolling Stones'

WHERE lower(artist_name) = 'the rolling stones';

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'Whitney Houston'

WHERE lower(artist_name) = 'whitney houston';Verify:

artist_name artist_standard

--------------------- --------------------

Led Zepplin Led Zeppelin

the rolling stones The Rolling Stones

OutKast OutKast

Outkast OutKast

Whitney houston Whitney HoustonFive dirty values, four clean artist names. The original artist_name column is untouched for auditing.

Fixing Inconsistent Decade Values

The || operator concatenates strings in PostgreSQL. Combined with simple WHERE clauses, it handles our decade problems:

Verify all decades are now consistent:

decade decade_count

---------- ------------

1970s 100

1980s 89

1990s 104

2000s 97

2010s 78

2020s 41Six clean decades. No duplicates, no abbreviations.

Removing Duplicate Albums

For the duplicate Beatles and Radiohead entries, we need to keep one and remove the other. First, identify which to keep:

Keep the one with the lower catalog_id (the first entry) and delete the duplicate:

DELETE 2Two rows removed. Verify the duplicates are gone:

Empty result. Clean.

UPDATE with Subqueries

You can use a subquery to determine which rows to update:

UPDATE with FROM

A more readable alternative for cross-table updates:

This joins music_catalog to genre_tags during the update and pulls the category value directly. Same result, cleaner syntax. This is PostgreSQL-specific and one of its nicest features.

UPDATE Patterns Summary

| Pattern | Use When |

|---|---|

SET col = value WHERE ... |

Simple fixes to specific rows |

SET col = col2 |

Copying between columns |

SET col = 'prefix' \|\| col |

String manipulation |

UPDATE t1 SET ... FROM t2 WHERE ... |

Joining tables during update |

UPDATE ... WHERE EXISTS (SELECT ...) |

Conditional update based on another table |

WHERE lower(col) = 'value' |

Case-insensitive matching |

Deleting Data ⌫

The DELETE Statement

DELETE removes rows from a table:

Warning

DELETE FROM table_name; without a WHERE clause deletes every row. Unlike dropping the table, the empty table structure remains, staring at you like a reminder of what you have done.

Deleting Rows by Condition

DELETE 12This removes all 12 albums released before the 1970s. PostgreSQL confirms the count, which you should always check against your expectation. If you expected 12 and got 12, good. If you expected 12 and got 412, less good.

DELETE vs DROP vs TRUNCATE

| Statement | What It Does | Reversible? |

|---|---|---|

DELETE FROM t WHERE ... |

Removes matching rows | Yes (in a transaction) |

DELETE FROM t |

Removes all rows, keeps structure | Yes (in a transaction) |

TRUNCATE t |

Removes all rows, faster than DELETE | No |

DROP TABLE t |

Removes table entirely | No |

Cleaning Up: DROP 🧹

Dropping Columns

After migration, remove temporary columns:

Clean tables are happy tables. Leftover columns named _copy, _backup, _temp, and _old are the database equivalent of packing boxes you never unpacked after moving.

Dropping Tables

Remove backup tables when you are confident the migration succeeded:

DROP TABLE is permanent. There is no undo. Make sure you are done with the backup before dropping it. Then wait a day. Then drop it.

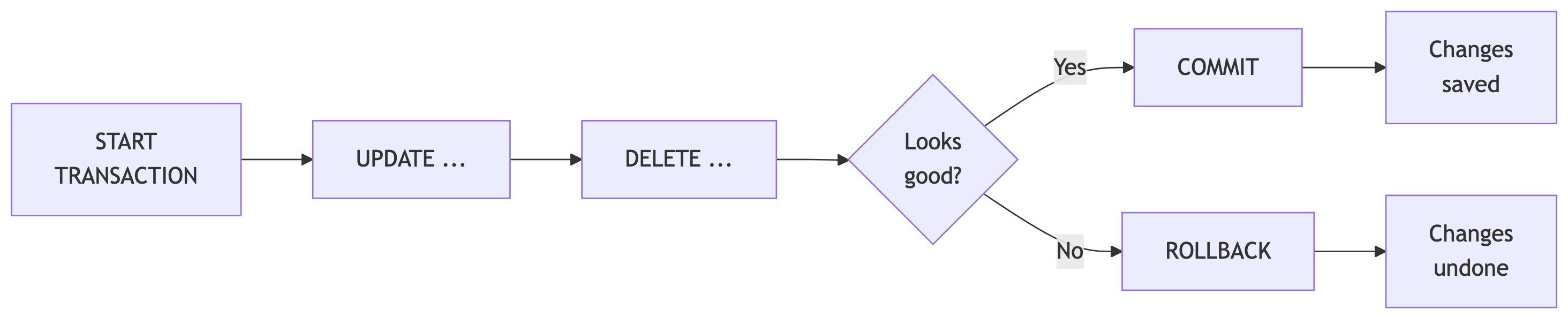

Transactions: Your Safety Net 🦺

What Is a Transaction?

A transaction groups multiple SQL statements into a single atomic unit. Either all of them succeed, or none of them do.

Transaction Syntax

Transaction Example: Catching a Typo

Check the result:

artist_name artist_standard

---------------- ----------------

Fleetwood Mac Feetwood Mac -- Typo!

Fleetwood Mac Feetwood Mac -- Typo!

Fleetwood Mac Feetwood Mac -- Typo!The typo is visible. Roll it back:

Query again:

artist_name artist_standard

---------------- ----------------

Fleetwood Mac Fleetwood Mac -- Original restored

Fleetwood Mac Fleetwood Mac

Fleetwood Mac Fleetwood MacThe ROLLBACK undid the UPDATE as if it never happened. Fleetwood Mac’s name is safe. This is why transactions exist.

When to Use Transactions

Always use transactions when:

- Running multiple related UPDATE or DELETE statements

- Making changes you want to verify before committing

- Working on production data

- Performing data migrations

The workflow:

START TRANSACTION;- Run your statements

SELECTto verify the resultsCOMMIT;if correct,ROLLBACK;if not

Tip

In psql, BEGIN is an alias for START TRANSACTION. You will see both in the wild. They do the same thing.

Transaction Gotchas

A few things to be aware of:

- DDL statements (

CREATE TABLE,DROP TABLE) in PostgreSQL are transactional. This is unusual. Most other databases auto-commit DDL. - If your session disconnects during an open transaction, PostgreSQL rolls it back automatically. Your data is safe, if slightly inconvenienced.

- Long-running open transactions can block other users. Do your work, then commit or rollback. Do not leave a transaction open while you go to lunch.

Data Migration: Putting It All Together ⋈

The Migration Workflow

With all these tools in hand, here is the complete workflow for migrating data from the staging table to our normalized music catalog:

INSERT INTO … SELECT

The key statement for migration copies data from one table to another:

DISTINCT ensures you do not insert duplicate rows. This is how you populate a lookup table from a denormalized staging table.

Migration with Foreign Keys

When migrating to tables with foreign key relationships, order matters:

START TRANSACTION;

-- 1. Populate parent table first (artists)

INSERT INTO artists (artist_name)

SELECT DISTINCT artist_standard

FROM music_catalog

WHERE artist_standard IS NOT NULL;

-- 2. Then populate child table with FK lookups (albums)

INSERT INTO albums (album_title, release_year, genre, label,

duration_min, artist_id)

SELECT DISTINCT m.album_title, m.release_year, m.genre, m.label,

m.duration_min, a.artist_id

FROM music_catalog m

JOIN artists a ON m.artist_standard = a.artist_name;

-- 3. Verify

SELECT count(*) FROM artists;

SELECT count(*) FROM albums;

COMMIT;Parent tables first, child tables second. Foreign key constraints will reject inserts in the wrong order.

Verifying the Migration

After committing, verify the data made it across cleanly:

-- Check counts

SELECT 'artists' AS tbl, count(*) FROM artists

UNION ALL

SELECT 'albums', count(*) FROM albums;

-- Spot-check with a JOIN

SELECT a.artist_name, al.album_title, al.release_year, al.genre

FROM albums al

JOIN artists a ON al.artist_id = a.artist_id

ORDER BY a.artist_name, al.release_year

LIMIT 10;If the JOIN returns the data you expect, the migration worked. If it returns nothing, your foreign keys are not aligned. Check the ON clause.

Backup and Swap Pattern

A safer migration pattern creates the new table, verifies it, then swaps:

-- Create backup with extra metadata

CREATE TABLE music_catalog_archive AS

SELECT *,

'2026-02-09'::date AS reviewed_date

FROM music_catalog;

-- Swap tables using RENAME

ALTER TABLE music_catalog

RENAME TO music_catalog_temp;

ALTER TABLE music_catalog_archive

RENAME TO music_catalog;

ALTER TABLE music_catalog_temp

RENAME TO music_catalog_archive;Three renames and the new table is live. The old one is still available as _archive if anything goes wrong.

Activity: Music Catalog Migration 🎧

The Scenario

You have the music_catalog staging table and the normalized artists and albums tables from the previous lecture. Your job: audit the staging data, fix the problems, and migrate the clean data into the normalized schema.

Part 1️⃣: Audit the Data (5 min)

Write queries to find all the quality issues. You should check for:

- Duplicate albums (same artist + title appearing more than once)

- NULL values in columns that should not be empty

- Inconsistent artist name spellings and casing

- Malformed decade values

Tip

Use GROUP BY ... HAVING count(*) > 1 for duplicates, IS NULL for missing values, and GROUP BY with ORDER BY to spot inconsistencies.

Part 2️⃣: Back Up and Fix (10 min)

Create a backup table

Add a safety column for artist names

Fix each category of issues using UPDATE and DELETE:

- Standardize artist name casing and fix typos

- Fill in NULL genres (research the albums if needed)

- Fix decade format inconsistencies (“1970” to “1970s”, “20s” to “2020s”)

- Remove duplicate album entries

Remember: one category at a time, verify after each fix.

Part 3️⃣: Migrate to Normalized Tables (10 min)

Write the migration wrapped in a transaction:

INSERT INTO artistsusingSELECT DISTINCTfrom the cleaned staging dataINSERT INTO albumswith a JOIN back toartistsfor the foreign key- Verify row counts

- COMMIT if correct, ROLLBACK if not

Tip

Parent tables first, child tables second. Your albums INSERT needs artist_id values, which means artists must be populated first.

One Possible Solution

-- Duplicates

SELECT artist_name, album_title, count(*)

FROM music_catalog

GROUP BY artist_name, album_title

HAVING count(*) > 1;

-- NULL genres

SELECT catalog_id, artist_name, album_title

FROM music_catalog

WHERE genre IS NULL;

-- Inconsistent artist names

SELECT artist_name, count(*)

FROM music_catalog

GROUP BY artist_name

ORDER BY artist_name;

-- Malformed decades

SELECT decade, count(*)

FROM music_catalog

GROUP BY decade

ORDER BY decade;-- Backup

CREATE TABLE music_catalog_backup AS

SELECT * FROM music_catalog;

-- Safety column

ALTER TABLE music_catalog ADD COLUMN artist_standard varchar(200);

UPDATE music_catalog SET artist_standard = artist_name;

-- Fix artist names

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'Led Zeppelin'

WHERE artist_name LIKE 'Led Zep%';

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'OutKast'

WHERE lower(artist_name) = 'outkast';

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'The Rolling Stones'

WHERE lower(artist_name) = 'the rolling stones';

UPDATE music_catalog

SET artist_standard = 'Whitney Houston'

WHERE lower(artist_name) = 'whitney houston';

-- Fix decades

UPDATE music_catalog SET decade = '1970s' WHERE decade = '1970';

UPDATE music_catalog SET decade = '2020s' WHERE decade = '20s';

-- Fix NULL genres (after research)

UPDATE music_catalog SET genre = 'Rock'

WHERE catalog_id = 'CAT-4501';

-- ... (remaining NULLs)

-- Remove duplicates

DELETE FROM music_catalog

WHERE catalog_id IN ('CAT-1004', 'CAT-2087');START TRANSACTION;

-- 1. Artists

INSERT INTO artists (artist_name)

SELECT DISTINCT artist_standard

FROM music_catalog

WHERE artist_standard IS NOT NULL

ORDER BY artist_standard;

-- 2. Albums

INSERT INTO albums (album_title, release_year, genre, label,

duration_min, artist_id)

SELECT DISTINCT m.album_title, m.release_year, m.genre,

m.label, m.duration_min, a.artist_id

FROM music_catalog m

JOIN artists a ON m.artist_standard = a.artist_name;

-- 3. Verify

SELECT 'artists' AS tbl, count(*) FROM artists

UNION ALL

SELECT 'albums', count(*) FROM albums;

COMMIT;-- Full picture

SELECT a.artist_name, al.album_title,

al.release_year, al.genre

FROM albums al

JOIN artists a ON al.artist_id = a.artist_id

ORDER BY a.artist_name, al.release_year;

-- Check constraints

SELECT * FROM albums WHERE release_year NOT BETWEEN 1900 AND 2100;

SELECT * FROM albums WHERE duration_min <= 0;Part 4️⃣: Discussion Questions

- What would happen if you tried to insert albums before artists? What error would you see?

- Why do we use

artist_standardfor the JOIN instead ofartist_name? - If an artist later changes their name, how many rows need updating in the normalized schema vs the original flat staging table?

- What would you add to make this migration idempotent (safe to run multiple times)?

Key Takeaways 🎁

The DML Toolkit

| Tool | When to Use |

|---|---|

UPDATE ... SET ... WHERE |

Fix specific data quality issues |

UPDATE ... FROM |

Update using data from another table |

DELETE FROM ... WHERE |

Remove rows that do not belong |

ALTER TABLE ADD/DROP COLUMN |

Reshape tables for cleaning |

INSERT INTO ... SELECT |

Migrate data between tables |

START TRANSACTION / COMMIT / ROLLBACK |

Wrap everything in a safety net |

The Data Engineer’s Checklist

Before any data modification:

- Audit the data thoroughly

- Create a backup (table or safety columns)

- Use transactions for multi-step changes

- Verify after every modification

- Keep the originals until you are certain

The goal is not speed. The goal is correctness. A fast migration that loses data is not a migration. It is a disaster with good performance metrics.

What Is Next

You now have the complete toolkit:

From raw CSV to a clean, normalized, constraint-enforced production database. The entire pipeline. Next, you will apply this pipeline end-to-end on your own with a new dataset.

References

Sources

DeBarros, A. (2022). Practical SQL: A Beginner’s Guide to Storytelling with Data (2nd ed.). No Starch Press. Chapter 9: Inspecting and Modifying Data.

PostgreSQL Documentation. “UPDATE.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/sql-update.html

PostgreSQL Documentation. “DELETE.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/sql-delete.html

PostgreSQL Documentation. “Transactions.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/tutorial-transactions.html

PostgreSQL Documentation. “ALTER TABLE.” https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/sql-altertable.html